The Last Days of the Dollar?

Re: The Last Days of the Dollar?

It is certainly an interesting article/blog, but I do not know what to make of it? I am not sure that the Fed is not draining liquidity in one place, while that liquidity is not being replaced elsewhere in the system.

However, the premise seems to be that if the Citigroups of the world cannot borrow at Fed's discount window at 3.50% because they do not have enough quality collateral then they have to recapitalize via expensive preference shares that carry an annual rate of interest of 11% and are covertible into Citigroup stock at some point in time.

I am sure all those like MBIA that has to issue new equity at a 14% discount to their existing beaten down share price would be quite happy to replenish their capital through the money markets, at 3.12% Libor plus a small spread, if that liquidity was available. But banks are hoarding it themselves because they have to maintain their own capital adequacy ratios (CADs).

One year Libor has been discounted to 2.75% now indicating that money markets are expecting at least another 0.25% Fed easing. But that does not mean that any further Fed easing will be reflected in lower borrowing costs for corporates as banks may increase spreads despite the lower Fed funds target rate. The Fed cannot control long-term rates. They can only set targets and hope banks will want, need or be able to borrow and lend at or near those benchmarks.

With 50 to 150 bankruptcies in the US banking sector forecast - especially to those involved in construction lending for example - the banks will unable and unwilling to pass through those lower lending costs until they know their own CAD levels are covered including any loan loss provisions on non-performing loans and possible bond defaults that banks also have to make provisions for as part of their CAD calculations.

Total net TIC flows were $60.4 billion vs. $65 bio f/c vs. $149.9 bio previously. Net long-term flows were $56.5 billion vs. $73.5 bio f/c vs. $90.9 bio previously. Foreigner are not lining up to buy USD denominated debt. The good news continues to surprise to the downside! ; - )

However, the premise seems to be that if the Citigroups of the world cannot borrow at Fed's discount window at 3.50% because they do not have enough quality collateral then they have to recapitalize via expensive preference shares that carry an annual rate of interest of 11% and are covertible into Citigroup stock at some point in time.

I am sure all those like MBIA that has to issue new equity at a 14% discount to their existing beaten down share price would be quite happy to replenish their capital through the money markets, at 3.12% Libor plus a small spread, if that liquidity was available. But banks are hoarding it themselves because they have to maintain their own capital adequacy ratios (CADs).

One year Libor has been discounted to 2.75% now indicating that money markets are expecting at least another 0.25% Fed easing. But that does not mean that any further Fed easing will be reflected in lower borrowing costs for corporates as banks may increase spreads despite the lower Fed funds target rate. The Fed cannot control long-term rates. They can only set targets and hope banks will want, need or be able to borrow and lend at or near those benchmarks.

With 50 to 150 bankruptcies in the US banking sector forecast - especially to those involved in construction lending for example - the banks will unable and unwilling to pass through those lower lending costs until they know their own CAD levels are covered including any loan loss provisions on non-performing loans and possible bond defaults that banks also have to make provisions for as part of their CAD calculations.

Total net TIC flows were $60.4 billion vs. $65 bio f/c vs. $149.9 bio previously. Net long-term flows were $56.5 billion vs. $73.5 bio f/c vs. $90.9 bio previously. Foreigner are not lining up to buy USD denominated debt. The good news continues to surprise to the downside! ; - )

The organized state is a wonderful invention whereby everyone can live at someone else's expense.

-

MrBill - Expert

- Posts: 5630

- Joined: Thu 15 Sep 2005, 03:00:00

- Location: Eurasia

Re: The Last Days of the Dollar?

MrBill,

Ronmn just posted in the Housing collapse thread that FGIA (sp?) was downgraded yesterday from AAA 6 notches to junk status. More to come on the monolines, after hearings yesterday in the US Congress on the matter. NY Governor said they needed major help in 4-5 days. Bowl swirling? Looks like it could, very quickly.

Ronmn just posted in the Housing collapse thread that FGIA (sp?) was downgraded yesterday from AAA 6 notches to junk status. More to come on the monolines, after hearings yesterday in the US Congress on the matter. NY Governor said they needed major help in 4-5 days. Bowl swirling? Looks like it could, very quickly.

-

patience - Resting in Peace

- Posts: 3180

- Joined: Fri 04 Jan 2008, 04:00:00

Re: The Last Days of the Dollar?

[quote="MrBill"]

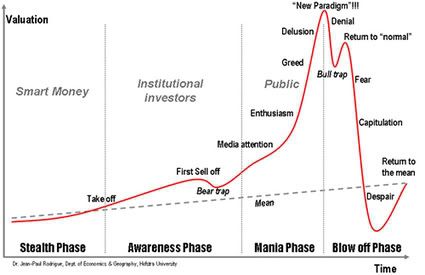

I'm not sure what purpose this comic has, but it seems to me it applies to Mr. Bill himself. In the 2.5 years that Mr. Bill has been a member of peakoil.com, he has written close to 4000 mostly long winded posts. I wonder if Mr. Bill can see himself in the cartoon.

Joined: Sep 15, 2005

Posts: 3930

Location: Eurasia

I'm not sure what purpose this comic has, but it seems to me it applies to Mr. Bill himself. In the 2.5 years that Mr. Bill has been a member of peakoil.com, he has written close to 4000 mostly long winded posts. I wonder if Mr. Bill can see himself in the cartoon.

Joined: Sep 15, 2005

Posts: 3930

Location: Eurasia

-

Euric - Tar Sands

- Posts: 622

- Joined: Sat 04 Dec 2004, 04:00:00

Re: The Last Days of the Dollar?

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('Euric', '')$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('MrBill', '

')

I'm not sure what purpose this comic has, but it seems to me it applies to Mr. Bill himself. In the 2.5 years that Mr. Bill has been a member of peakoil.com, he has written close to 4000 mostly long winded posts. I wonder if Mr. Bill can see himself in the cartoon.

Joined: Sep 15, 2005

Posts: 3930

Location: Eurasia

')

I'm not sure what purpose this comic has, but it seems to me it applies to Mr. Bill himself. In the 2.5 years that Mr. Bill has been a member of peakoil.com, he has written close to 4000 mostly long winded posts. I wonder if Mr. Bill can see himself in the cartoon.

Joined: Sep 15, 2005

Posts: 3930

Location: Eurasia

Yes, I like to laugh at myself and anything else that I find particularly funny or ironic. Like you say, my posts are too long and afterall a picture is worth a thousand words. I thought you would appreciate my effort to economize? Whereas you mostly post articles that are simply copy & paste, and reflect nothing about your own thought process other than you hate America. Whatever Euric, fortunately your opinion means less than nothing to me. Have a nice weekend anyway! ; - )

The organized state is a wonderful invention whereby everyone can live at someone else's expense.

-

MrBill - Expert

- Posts: 5630

- Joined: Thu 15 Sep 2005, 03:00:00

- Location: Eurasia

Re: The Last Days of the Dollar?

MrBill,

I'm guessing we have a short term flight-to-quality to US debt, vs a long term aversion to US debt, or bonds, the longer the term, the more aversion, based upon:

1) Smart money is worried about monolines, equities and bank troubles.

2) Nobody knows how this will play out, so there is risk to long term anything.

3) Commodities are bubbling away, and look risky to me.

Meanwhile, the FED, the US Treasury, govt, and major banks are desperately playing hide-the-sausage to buy time, hoping for a miracle as they watch the debt bubble collapse. The politicos want to put it off until after elections, and the banks want to put off the reckoning forever, AKA, Japan.

I want to be as risk averse as possible, so when I became aware of the banking mess, I dumped ALL the paper investments some time ago and went to cash. The longer it sits there, the more we lose to price inflation, monetary/credit deflation notwithstanding. So, we bought food, and such things as we will need for the short term future. PM's look like they could go any direction to me, so we have avoided that. Until recently, I would have put some about half of our cash into muni bonds, but that is coming unwrapped as we speak. I only mention that as a reference for my goal here. I could put some money into steel for retail sale in our small business, but it has gone up 30% in the last couple months.

Does a safe harbor exist for spare cash? There are as many opinions on the future as there are belly buttons. I want to sit on the sidelines, without speculating, if that is possible. If not, I'll take my best shot at it, since doing nothing is also a decison.

I'm guessing we have a short term flight-to-quality to US debt, vs a long term aversion to US debt, or bonds, the longer the term, the more aversion, based upon:

1) Smart money is worried about monolines, equities and bank troubles.

2) Nobody knows how this will play out, so there is risk to long term anything.

3) Commodities are bubbling away, and look risky to me.

Meanwhile, the FED, the US Treasury, govt, and major banks are desperately playing hide-the-sausage to buy time, hoping for a miracle as they watch the debt bubble collapse. The politicos want to put it off until after elections, and the banks want to put off the reckoning forever, AKA, Japan.

I want to be as risk averse as possible, so when I became aware of the banking mess, I dumped ALL the paper investments some time ago and went to cash. The longer it sits there, the more we lose to price inflation, monetary/credit deflation notwithstanding. So, we bought food, and such things as we will need for the short term future. PM's look like they could go any direction to me, so we have avoided that. Until recently, I would have put some about half of our cash into muni bonds, but that is coming unwrapped as we speak. I only mention that as a reference for my goal here. I could put some money into steel for retail sale in our small business, but it has gone up 30% in the last couple months.

Does a safe harbor exist for spare cash? There are as many opinions on the future as there are belly buttons. I want to sit on the sidelines, without speculating, if that is possible. If not, I'll take my best shot at it, since doing nothing is also a decison.

-

patience - Resting in Peace

- Posts: 3180

- Joined: Fri 04 Jan 2008, 04:00:00

Re: The Last Days of the Dollar?

I have been overweight cash now for quite sometime and share many of the concerns that you have. One I find most asset prices over-valued. And secondly I am worried about inflation in the long-term, so that cash needs to be deployed eventually. Normally, commodities would be the place to go for protection, but many commodity prices are also very high. There are a lot of places one could have invested two years ago, but that is of little help now.

I sold most of my non-core equity positions last summer/early autumn, and have been underweight stocks ever since. I have some core energy holdings, but about one-third my normal size. I believe this market will take a year or two to unwind, and that we have not seen the lows, yet, this year. Therefore, I am testing the waters, but only in small amounts, while keeping a list of stuff I would like to buy if the prices came back to 'normal' by historical or relative standards.

Two-thirds to three-quarters of the my assets are not in US dollars, but in euros mainly, and some Sterling and Canadian dollars. But even here the problem is finding something worthwile to buy? I have gone into German government bonds - bunds - as protection. They are still yielding near 4% in the 10y and will protect me against US dollar weakness. I also expect the ECB to start easing later in 2008.

However, that still leaves me over-weight in cash. I have twice as many bonds as equities. And twice as much cash as bonds. I have been paying down any outstanding debt - such as my mortgage - just because I cannot find anywhere else to deploy that money at moment. I would like to own more farmland, but that is another story. Prices there are not cheap either. And I am reluctant to overpay above and beyond what the land can actually produce. That would be, well, speculation on land prices. This is the time for capital preservation and not speculating.

I have instead been trading FX to take advantage of movement there without committing myself to anything in particular. Mostly I am trying to hedge any downside, by shifting from euros into, say Canadian dollars, if the price looks overdone one way or the other. More technical trading. However, last week was a loser for me. I made some money being long CAD against the USD, but lost being short EUR/JPY as risk takers put their yen carry trades back on. Also, JPM put out a report last week saying that yen was not likely to revalue as much as people thought, and that the market was overweight long yen in anticipation of yen strengthening.

I keep my positions deliberately small at the moment, so they cannot hurt me per se, but I still like to be right and get the market timing correct. That was not very successful last week, but I can take comfort knowing that if my short-term trades do not workout properly that my underlying position is larger, so net/net I am still on the right side of the trend.

But I share your concerns. Cash is undervalued, and if not for the threat of public policy induced inflation from excessive money supply growth and currency devaluation then I would be happy to sit on the sidelines and wait. Everything else is a speculative punt at the moment. Gold may hit the moon, but then again maybe it won't? Not with my money thank you very much! ; - )

I sold most of my non-core equity positions last summer/early autumn, and have been underweight stocks ever since. I have some core energy holdings, but about one-third my normal size. I believe this market will take a year or two to unwind, and that we have not seen the lows, yet, this year. Therefore, I am testing the waters, but only in small amounts, while keeping a list of stuff I would like to buy if the prices came back to 'normal' by historical or relative standards.

Two-thirds to three-quarters of the my assets are not in US dollars, but in euros mainly, and some Sterling and Canadian dollars. But even here the problem is finding something worthwile to buy? I have gone into German government bonds - bunds - as protection. They are still yielding near 4% in the 10y and will protect me against US dollar weakness. I also expect the ECB to start easing later in 2008.

However, that still leaves me over-weight in cash. I have twice as many bonds as equities. And twice as much cash as bonds. I have been paying down any outstanding debt - such as my mortgage - just because I cannot find anywhere else to deploy that money at moment. I would like to own more farmland, but that is another story. Prices there are not cheap either. And I am reluctant to overpay above and beyond what the land can actually produce. That would be, well, speculation on land prices. This is the time for capital preservation and not speculating.

I have instead been trading FX to take advantage of movement there without committing myself to anything in particular. Mostly I am trying to hedge any downside, by shifting from euros into, say Canadian dollars, if the price looks overdone one way or the other. More technical trading. However, last week was a loser for me. I made some money being long CAD against the USD, but lost being short EUR/JPY as risk takers put their yen carry trades back on. Also, JPM put out a report last week saying that yen was not likely to revalue as much as people thought, and that the market was overweight long yen in anticipation of yen strengthening.

I keep my positions deliberately small at the moment, so they cannot hurt me per se, but I still like to be right and get the market timing correct. That was not very successful last week, but I can take comfort knowing that if my short-term trades do not workout properly that my underlying position is larger, so net/net I am still on the right side of the trend.

But I share your concerns. Cash is undervalued, and if not for the threat of public policy induced inflation from excessive money supply growth and currency devaluation then I would be happy to sit on the sidelines and wait. Everything else is a speculative punt at the moment. Gold may hit the moon, but then again maybe it won't? Not with my money thank you very much! ; - )

The organized state is a wonderful invention whereby everyone can live at someone else's expense.

-

MrBill - Expert

- Posts: 5630

- Joined: Thu 15 Sep 2005, 03:00:00

- Location: Eurasia

Re: The Last Days of the Dollar?

I am investing in cast iron cookware. Seriously, I am. I figure that there is no downside. If the value goes down, I eat out of them. I bought the Griswold and Wagner book and am scouring yard sales from here to New Hampshire.

I think cast iron is the new precious metal.

It can't go down like the dollar.

You can make yummy things in it, even if the electricity goes out.

Here's a site about it:

http://www.griswoldandwagner.com/

Check out those prices.

It's the ultimate in a tangible asset.

I think cast iron is the new precious metal.

It can't go down like the dollar.

You can make yummy things in it, even if the electricity goes out.

Here's a site about it:

http://www.griswoldandwagner.com/

Check out those prices.

It's the ultimate in a tangible asset.

Deep in the mud and slime of things, even there, something sings.

-

Revi - Light Sweet Crude

- Posts: 7417

- Joined: Mon 25 Apr 2005, 03:00:00

- Location: Maine

Re: The Last Days of the Dollar?

MrBill, why not park some in Australian bonds?

Yields should be OK and currency should strengthen further against US and EU + many other european if they start cutting rates there.

(Or do you think AUD will drop like a rock if the slow down continues?)

Yields should be OK and currency should strengthen further against US and EU + many other european if they start cutting rates there.

(Or do you think AUD will drop like a rock if the slow down continues?)

- Micki

Re: The Last Days of the Dollar?

..Since this thread is supposedly about the "last days of the dollar," here's an interesting and extremely candid analysis by an "economist and banker" in Iran - apparently they are much more candid than the economic pundits heard here in the US regarding the current state of affiars...

http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php? ... a&aid=8108

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('', '[')b]The Fall of the Dollar Empire

by Hamid Varzi

Global Research, February 17, 2008

Press TV, Tehran

An interview with Hamid Varzi by Monavar Khalaj

The following is an interview with Hamid Varzi an economist and banker based in Tehran about the US economic crisis.

Q.Please tell us more about the 2007 subprime mortgage financial crisis and why, how and when it began?

A.The crisis began in 2000 with Bush Jr.’s election that re-established the irresponsible “Supply Side” and “trickle-down” economic policies of the Reagan years. We are wrong to focus only on the subprime crisis, which has been conveniently blown out of all proportion in order to create the convenient and comforting impression that this is a manageable problem solvable through a simple reduction in interest rates and a 90-day government mandated delay on foreclosures (Hillary’s recommendation).

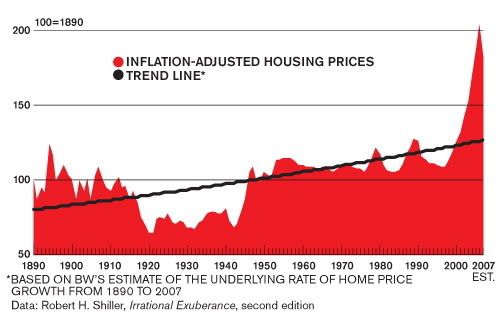

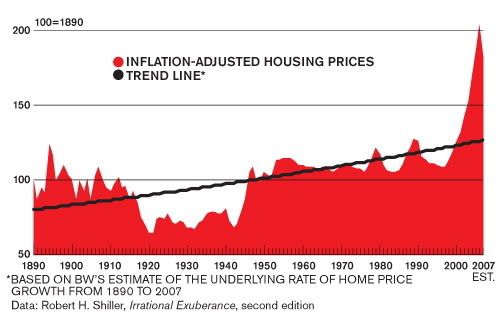

The subprime crisis presages far greater problems down the road. It is already spreading to other forms of commercial paper, and even if the damage can be contained the relief will be only temporary because a much larger danger is looming on the horizon: The US economy has grown largely on the back of speculative credit derivatives that have risen exponentially to $35 trillion, which is more than double the size of the entire US economy! This is an approaching iceberg, and all you’ve seen (in the sub-prime scandal) is the tip. To return to your question, the first chart below proves that speculative commercial lending received a major boost with Bush’s election, and soared with his re-election.

Credit derivative volumes continue to soar. The notional principal outstanding of credit default swaps (CDSs) grew 33% in the second half of 2006, rising from $26 trillion to $34.5 trillion, following 52% growth during the first half of 2006, according to industry body International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). (Global Finance, June 2007). The ECB confirms the HI 2006 figure of $ 26 trillion. As you will observe, actual growth has far exceeded even the rapid growth foreseen by the British Bankers’ Association Credit Derivatives Report 2006 in which ambitious growth targets for 2008, forecasted below, have already been met. The bulk has been ‘created’ in and by the United States, and only a small portion of this speculative debt relates to subprime mortgage lending.

http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php? ... a&aid=8108

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('', '[')b]The Fall of the Dollar Empire

by Hamid Varzi

Global Research, February 17, 2008

Press TV, Tehran

An interview with Hamid Varzi by Monavar Khalaj

The following is an interview with Hamid Varzi an economist and banker based in Tehran about the US economic crisis.

Q.Please tell us more about the 2007 subprime mortgage financial crisis and why, how and when it began?

A.The crisis began in 2000 with Bush Jr.’s election that re-established the irresponsible “Supply Side” and “trickle-down” economic policies of the Reagan years. We are wrong to focus only on the subprime crisis, which has been conveniently blown out of all proportion in order to create the convenient and comforting impression that this is a manageable problem solvable through a simple reduction in interest rates and a 90-day government mandated delay on foreclosures (Hillary’s recommendation).

The subprime crisis presages far greater problems down the road. It is already spreading to other forms of commercial paper, and even if the damage can be contained the relief will be only temporary because a much larger danger is looming on the horizon: The US economy has grown largely on the back of speculative credit derivatives that have risen exponentially to $35 trillion, which is more than double the size of the entire US economy! This is an approaching iceberg, and all you’ve seen (in the sub-prime scandal) is the tip. To return to your question, the first chart below proves that speculative commercial lending received a major boost with Bush’s election, and soared with his re-election.

Credit derivative volumes continue to soar. The notional principal outstanding of credit default swaps (CDSs) grew 33% in the second half of 2006, rising from $26 trillion to $34.5 trillion, following 52% growth during the first half of 2006, according to industry body International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). (Global Finance, June 2007). The ECB confirms the HI 2006 figure of $ 26 trillion. As you will observe, actual growth has far exceeded even the rapid growth foreseen by the British Bankers’ Association Credit Derivatives Report 2006 in which ambitious growth targets for 2008, forecasted below, have already been met. The bulk has been ‘created’ in and by the United States, and only a small portion of this speculative debt relates to subprime mortgage lending.

...with that broad stage set, here's what he said about the fall of the dollar....

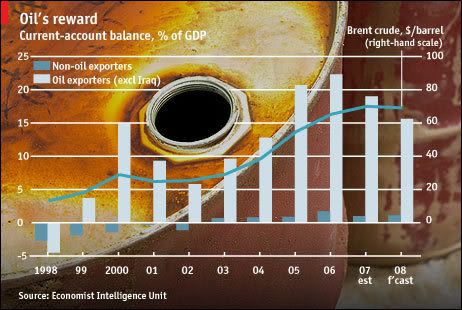

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('', 'Q').Why has the US Dollar gone into a spiral of decline?

A.Mainly because it has to borrow $3 billion[s] each and every day from foreigners to finance its massive current account deficit and its war machine. Foreign nations have become nervous at the annual 10% deterioration in their Dollar holdings. Foreigners don’t even need to reduce their Dollar reserves to precipitate a Dollar crisis; they can do so merely by refusing to increase their holdings, i.e., refrain from participating in further US Treasury auctions. {For the past few months I think we have been seeing evidence of this very phenomenon....}

Q.There are two views about the impact of the dollar decline on the US economy: one holds that it would eventually benefit the US economy through boosting exports while others believe that it damage the US economy. What is your opinion?

A.The export view is sheer unadulterated nonsense. The Dollar has been in fundamental decline since the end of WWII, as has its trade deficit!!! A weak currency is not a panacea for economic health. It merely delays the inevitable drive to increase competitiveness, as demonstrated by Germany which has again become the world’s No. 1 exporter despite an 80% appreciation in the Euro since 2001! The drop in the Dollar has, on the contrary, caused only a minimal reduction of its annual $750 billion trade deficit, which proves that US lack of competitiveness is truly endemic and not a function of exchange rates.

A weak currency also boosts inflation as imports become more expensive. In America’s case it represents a ‘double whammy’ because, while imports become more expensive they are unavoidable since the US doesn’t produce many of the consumer goods it needs.

...now that was a refreshingly honest assessment about the systemic problems that negate the "anti-Chinese"/yuan revaluation rhetoric that US policy makers regularily use as the simply-minded "solution" to the US's massive current accout deficit....but I digress...

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('', 'Q').Would the dollar’s depreciation lead other countries to switch to other main currencies and given that the US Dollar is a fiat currency could such a move further fuel the dollar’s decline?

A.They already have! Countries are realizing (ours a little late, but better late than never!) that the US Dollar is in fundamental imperial decline: From a peak of 121 shortly after Clinton left office the Dollar index has been swooning with no end in sight. Yes, Reagan boosted the Dollar temporarily, but only by raising the Prime Rate to a massive 21.5% to attract foreign aid (sorry, foreign ‘capital’)! Here is another chart, this time of the Dollar’s seemingly unstoppable decline against a basket of international currencies (trade-weighted index):

Q.What will be the impacts of the US dollar decline on Iran’s economy?

A.Not much. Iran’s own economic policies (or lack of) influence our nation’s economic health far more significantly than the Dollar exchange rate.

Q. What will be the impacts of the US presidential elections on the US economy?

A.There will definitely be a massive change, with a return to the much maligned ‘Clintonomics’ if either Hillary or Obama wins, as I personally predict. The Dollar will strengthen, by which I mean that it will reverse some of its losses, but not that it will re-emerge as the fiat currency. The deterioration in the US fiscal and current account deficits will be stemmed as the US increases taxes, reduces budget wastage, redistributes wealth more fairly and severely reduces military spending on the back of a partial or withdrawal from Iraq which has already cost $2 trillion according to 2001 Nobel Economics Prize Winner Joseph Stiglitz.

If McCain wins, after a brief relapse the Euro will strengthen to $2.00 from its current rate of $1.48, because McCain will be just another Republican spendthrift unable to offload the party baggage (the “special interests”), no matter how ‘fiscally responsible’ he sounds on the surface. But I doubt he will win.

Q.Do you think the Iranian decision to cut its ties with the greenback and Tehran’s call on its importers of crude to pay in non-dollar currencies have adversely contributed to the Dollar nosedive?

A.Definitely, because it was not so much the nominal sums involved, which are paltry by global comparison, but the psychological effect of the move which encouraged others to follow suit.

Q.Should one consider the US crisis as an opportunity for booming economies like India and China to assume a more important role in the world’s markets?

A.They already have. The US is totally dependent on China’s goodwill. If the US were to ban all imports from China tomorrow morning the US economy would suffer a heart attack as it would have to import those same goods more expensively from elsewhere. In retaliation, the Chinese would sell their surplus Dollar mountain and precipitate a global economic depression. The emerging economies would be better able to withstand such an Armageddon scenario because they are accustomed to hardship, while decadent US consumers are already bankrupt despite an environment of extended global economic growth. The US would probably suffer riots, internal conflict and starvation for the first time in 80 years. Emerging economies are used to economic hardship and even war. The US is much more fragile than its leaders and economic pundits admit. There is a huge fundamental and conceptual difference between a) going from recession to depression (the USA), and b) going from 10% + economic growth to a more reasonable 3% economic growth (Russia, India, China, ….)

...wow, he didn't even mention Peak Oil, but like I mentioned, this is a rather candid analysis of the dollar and the associated problems that are slowly unfolding....

Last edited by Petrodollar on Mon 18 Feb 2008, 23:07:52, edited 1 time in total.

-

Petrodollar - Coal

- Posts: 406

- Joined: Tue 19 Jul 2005, 03:00:00

- Location: Maryland