Trader's Corner 2007

Re: Trader's Corner 2007

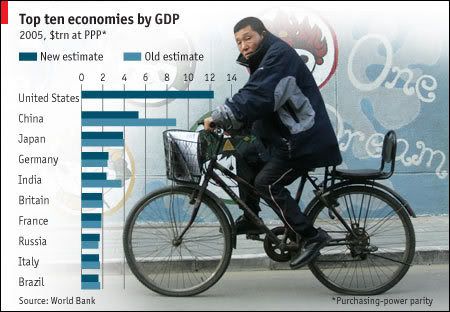

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('Daryl', 'U')S public (government debt) -the traditional big bad national debt figure - is estimated at about $5 trillion or around 65% of GDP. This figure has averaged about 40% of GDP since WW2. It is the 35th worst percentage worldwide among governments. Japan's public debt, for example, is 177% of GDP, France's is 66% of GDP and UK's is 43%. I got most of these figures from the CIA World Fact Book and the most recent Federal Reserve Flow of Funds Report.

$5 trillion debt is low balling it there Daryl, but I'll agree with the 65% of GDP figure. same source CIA World Fact Book USA now ranked 26...we're moving up the list!

Anyways I'd like to state that not all debts are created equal. Much depends on what the debt is for. For example getting into debt to create a national highway system has benefits. Freeways make it easier to transport goods and services so there's a potential for a positive economic result.

However getting into debt to fight a losing WAR is a bad investment.

--------

BTW I would prefer a balanced budget (much to the chagrin of Keynesian economic cheerleaders) but that can be saved for another thread.

- cube

- Intermediate Crude

- Posts: 3909

- Joined: Sat 12 Mar 2005, 04:00:00

Re: Trader's Corner 2007

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('', 'F')or example, it is rarely pointed out that the published personal savings rate in the US is very misleading. In fact US household net worth has been rising steadily for quite a long time and last year reached a (even in percentage terms) staggering $29.1 trillion, a figure that doesn't even include home equity, but does include all mortgage liabilities.

I'm probably going to be laughed at for saying this (especially the first five words), but...

In my Econ 101 class, my professor noted that savings rates fail to include education as a form of saving and is instead usually labeled under consumption. He considers it, fairly rightfully so I imagine, a form of savings because of the intellectual and mental investment in the students and their futures.

Now, I don't think it'd be fair to say that all tuitions paid are a form of investment. Any degree at Bob Jones University should be considered an investment towards the future; being an idiot isn't really an economically productive occupation. Certain degrees at major universities such as communication couldn't be included either as they are mostly taken up by jocks and kids looking for easy access to parties.

Aside from an engineering, sciences, or, yes, economics major at a university or college, investment into books should also be included. Mind you, they should be intellectual books and periodicals: textbooks, analysis, reports, academic journals, etc.

I guess because each one has to be taken on a nearly individual basis and there are hundreds of degrees and millions of books and periodicals, it's simply not practical to do a comprehensive savings rate analysis of the US.

Then again, he blew off any assertion that we're headed towards bad times in the future due to our massive debt (and I imagine he has no clue about PO), so he's clearly fallible.

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('', 'I') think maybe sometimes we need to lean against a natural tendency we humans have toward pessimism

It's a bit of a defense mechanism, I guess. If you're pessimistic, and then things go poorly, then you've already prepared yourself mentally and hopefully in real life through reducing your lifestyle or whatever. But if things go well, then you've made out tremendously.

On the flip side, if you're optimistic constantly, and then you get what you want, well, you're still a bit disappointed. Humans are a species about surprise and always doing better. Perception is Reality, right? So if you've thought in your mind that something is going to happen and it does, then nothing has really changed.

Now if the situation goes awry, then you're really screwed mentally.

I'd rather be prepared mentally for anything bad on the horizon. If PO or whatever comes crashes towards me, I'd love to look at it and go "Meh." and hit the snooze. I don't like freaking out over anything.

----

I really like this thread. Never been here before until I talked to Bill. Much better than those racism threads.

I want to put out the fires of Hell, and burn down the rewards of Paradise. They block the way to God. I do not want to worship from fear of punishment or for the promise of reward, but simply for the love of God. - Rabia

- mekrob

- Expert

- Posts: 2408

- Joined: Fri 09 Dec 2005, 04:00:00

Re: Trader's Corner 2007

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('', 'I')f you're pessimistic, and then things go poorly, then you've already prepared yourself mentally and hopefully in real life through reducing your lifestyle or whatever. But if things go well, then you've made out tremendously.

I could refer you to the ending of the recent Stephen King movie "The Mist".

To be more specific, a pessimistic society will refrain from investing in the future by expanding capital, labor, and skill sets, since any investment that is not survivalist becomes worthless if things go awry. In a sufficiently complex economy, pessimistic expectations can often become self fulfilling.

For example, if everyone comes to believe there will not be enough gasoline then everyone will rush to the gas station and fill up their storage tanks in an effort to hoard. If the government interferes with either price controls or price gouging regulations then hoarding induced shortages will spread, leaving no choice but to introduce rationing faced with widespread economic dislocation without any real supply disruption.

-

LoneSnark - Tar Sands

- Posts: 514

- Joined: Thu 15 Nov 2007, 04:00:00