Page added on February 28, 2011

Peak Oil Blues: Depression isn’t Sadness

Clinical depression is one of those illnesses that, despite the increasing evidence of its absolutely devastating impact on the physiology of the brain, continues to be thought of as a failure of fortitude or spirit. Depression is “contagious,” and is not only hard on those who are depressed, but everyone who cares about them, as well. Depression destroys intimate relationships, and makes parenting exceedingly difficult. By some estimates, in 40% of those divorcing, at least one of them is depressed. I’m going to do my best, in the next 3000 words, to share with you what depression is, and how I’ve experienced it personally. At this point, I’m able to do it, and have chosen to do it now, when the effects of my depressive episode have not completely lifted, so I can still be closely in-touch with this”Devious Crippler.”

Some General Facts

Depression is the leading cause of disability world-wide, and the number one cause of suicide. Depression is found all over the world, although it may be reported differently in different cultures. In China and other Asia countries, for example, depression may be reported more as weakness, tiredness or “imbalance.” In Latino or Mediterranean cultures, complaints of “nerves” and “headaches” are more common. Those in the Middle East report “problems of the heart” while Hopi report being “heartbroken.”

Women suffer clinical depression at twice the rate men do, especially in the US and Europe, but for Bipolar illness, another mood disorder, the rates are roughly equal. I’ll be talking here about Major Depressive Disorder (MDD).*

Children and adolescents also experience MDD, but their symptoms are different: Children report more somatic complaints, irritability, and social withdrawal, and less hypersomnia (sleeping alot) and slow motor movements. In fact, any parent concerned about a teen or a child being depressed, cranky, or doing poorly in school, should make sure they are getting plenty of sleep. Teens go through a biological phase that shifts their melatonin release, where even if they want to be in bed by 10 pm, they likely will be unable to fall asleep and will still wake up drowsy the next morning if it is too early. While start time for high schools still remains earlier than grammar school, an adolescent should be able to get more sleep later into the morning than younger children, but most often don’t.**

Causes

Depression doesn’t have a single etiology (cause). There are many, and we are still learning about them. We know that early life trauma, including physical neglect or abuse, as well as later adversity and stressful life events contribute to the development of depressive episodes. So can a family history of depression (genetic predisposition), although not all people who have depressed relatives end up experiencing depression themselves. Insults to the brain cells can also bring on a depression. An absence of “social support” can also make a person vulnerable to depression when stressed, just as a strong supportive network can help ward off its harmful effects, but, as I’ll talk more about below, it can be hard to be a support person to someone who is depressed.

A Developing Understanding of the Physiology and Biochemistry of the Brain

Research into the biology of depression is challenging and multifaceted. Anatomical damage, neuronal pruning and sprouting, and new cell growth are just some of the areas being investigated, as well as the etiologies mentioned above. It isn’t the stress, but the stress hormones that are increasingly being looked at. Some researchers compare the postmortem brains of depressed and non-depressed individuals to discover clues. Others compare PET scans of the same subjects when they are depressed, and after they’ve recovered. Animal studies are also conducted in an attempt to duplicate similar biochemical conditions. There are other types of research. Each method of study will produce differences, so generalizing about the biology of depression is difficult. My goal here is to paint you a picture, not provide a comprehensive scientific explanation of what we know.

Many researchers think that Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) shrinks a section of the brain called the hippocampus, even with the first depressive “episode,” but they disagree whether that damage is permanent. Messing with the hippocampus is particularly damaging because the hippocampus generates new nerve cells, a process called neurogenesis. We also know that lots of glial cells in the brain (Albert Einstein had a ton…) is better than less, and that depression probably messes with them as well.

Prolonged stress causes dysregulation in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and may contribute to the pathological source of MDD. But stress, by itself, doesn’t cause depression. There’s even a good kind of stress (eustress), like going on vacation, that can be hard for some people to handle, while other people find it all part of the fun.

One of the many chemicals overproduced by stress is called “cortisol.” Cortisol is very necessary for bodily functioning, but can also have harmful impacts on the brain and body in large doses because it damages the cells of the hippocampus. It can both helps to facilitate emotional memories as well as impair learning, depending on the level. There is also a connection found between chronic stress, weight gain, and diabetes that implicates stress and cortisol. Cortisol impacts the reproductive system, resulting in an increased risk of miscarriage and (in some cases) temporary infertility.

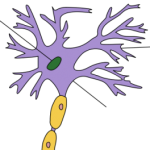

I think of high levels of cortisol as a sort of “ammonia in the mind,”  that acts as “tree pruners” that cut back on the dendrites that make up the tree-like structure of the brain. That’s not a good thing. Those tree branches help send chemical “messages” through the brain. Soak them in “ammonia” and you cut down their capacity to communicate effectively with each other.

that acts as “tree pruners” that cut back on the dendrites that make up the tree-like structure of the brain. That’s not a good thing. Those tree branches help send chemical “messages” through the brain. Soak them in “ammonia” and you cut down their capacity to communicate effectively with each other.

I’m taking liberties, here, but hopefully you get the idea.

The Depressive’s Mind

Depression does weird things. It helps you remember negative things really well, but when you’re depressed, it is much harder to remember the positive things that accompany them. In other words, you don’t see the complete picture. This might be because positive or neutral memories get processed by the hippocampus, (that gets slammed when you are depressed). And, like all disorders that mess with your mind, you don’t know that what you are thinking and feeling is a distortion. You just assume it is reality.

Your reality.

Your sucky, horrible, endlessly miserable reality.

Depressed people talk about killing themselves not because they want to be dead, but because they want toescape this state. And contrary to popular opinion, you don’t “plant the idea in a person’s mind” by asking whether or not they are suicidal. You should take a person seriously when they talk about committing suicide. Depression and alcohol are fatal mixtures when a person is suicidal.

When depressed, a person will talk about quitting the job they “hate” or divorcing the spouse they “can’t stand,” but then dumbfound their friends by dismissing these feelings when they are no longer depressed. They’ll say things like “No job is perfect, but mine works for me.” or “I was just being hard on him. I love my husband. He’s quirky, but what’s wrong with that?”

One woman, when her depression lifted, was angry at her psychiatrist for “siding with my depression against me.” She felt that he had too willingly entertained her distorted thoughts–taken them seriously–to her detriment. It shocked him, but he understood her point. For someone in the grips of their first deep depression, telling them: “That’s your depression talking” might feel insulting and dismissive. Not at all “supportive.” But to someone who has been through the cycle of depression, recovery, depression, they might find such a statement comforting. It may mean: “Don’t take that thought too seriously. I know you believe it, but you are being tricked by your brain into feeling that, much like an hallucinogen creates images that aren’t there.“ It is a fine line for a mental health professional or anyone else for that matter, to walk. It can be taken as dismissive or supportive-the quality of the relationship between people is the important ingredient.

Relationships On Depression

A depressed spouse (DS) is a lousy companion. They are argumentative, hostile, tearful, exhausted and joyless. In functional marriages that have a depressed spouse, (most often the woman,) she is angry and irritable, while the husband is not. In a problematic marriage with a depressed spouse, both are hostile. While “social support” is extremely helpful, it is also hard to be supportive of a depressed person. They are so…well,depressing. As I’ve said, depression is contagious. And depression has no saving grace. The best thing you can learn from struggling with depression is how to avoid it.

It is normal to look for reasons why one may be feeling depressed, and too often the blame is laid on the doorstep of the Non-Depressed Spouse (NDS.) DS’s can see all the negative features of their spouses, but none of their redeeming qualities. As every couple has what John Gottman calls a set of “perpetual problems,” we all have things we can ruminate and complain about. Sixty-nine percent of marital problems are “perpetual” according to Gottman, meaning: “Okay, you’re not happy about it but you learn you can cope with it, have a sense of humor about it, and be affectionate even while you are disagreeing, and soothe one another, de-escalate the conflict.” But when one spouse is depressed, humor is a hard thing to come by. Every fight is a matter of life or death, and a hopeless reminder of how terrible everything is.

Many depressed people suffer from an interesting word called “anhedonia.” It is a Greek word that means “without pleasure.” What’s fun? Nothing, to the DS. Normally pleasurable life events such as eating, exercise, social interaction, or sexual activities lose their appeal. Vacations? “What’s the point?“ Dinner and a movie? “Save your money, you don’t want to be with me anyway.“ Any effort exerted by the NDS to help “pull them out of it” is met with resistance. The DS withdraws from the world, leaving the NDS on the horns of a dilemma:

- If the NDS socialize alone, they will be blamed for “abandoning” their DS.

- If they don’t, they’ll feel their own social isolation and resentment.

- Dragging their DS out will assure them of lousy, critical company.

The once entertaining and engaging partner has been replaced by a dour, complaining, exhausted, bump-on-a-log….who hates themselves for being like this, but seems unwilling (or unable) to change.

DS can disrupt the bedroom with either too little sleep, disturbed sleep (waking up in the middle of the night or too early in the morning), or too much. Interest in a sex life plummets, or sex becomes one of the few outlets that temporarily alleviates their mood. DS’s can be very lethargic, or nervous and anxious. They can stop eating, or over-eat without pleasure. “Carbo-craving” is common.

They forget the important errand they promised to run because memory is impaired, and can’t make a decision, or read a book to relax.

Domestic and parenting duties shift, and the NDS begins assuming more of the load. But this often intensifies the low self-assessment, crippling guilt and hostile internal feelings of the depressed spouse. They may feel “I’m useless. I can’t even cook now.” Often, instead of being grateful to the NDS for the help, the DS becomes even more hostile, as their own negative internal voices intensify.

While the NDS may initially be understanding and sympathetic of their partner, the DS looks intently for any evidence of resentment, and may even provoke their partner, in order to demonstrate it. Once expressed, it becomes further “evidence” of the DS’s “worthlessness.” They read “rejection” in actions where it is not there, and often dismiss efforts to comfort and support as “patronizing” or “insincere.” When the NDS does blow up, it is evidence that “you felt that way all along.”

Remarkably, because depressed people are so sensitive to social rejection, the explanation for the social withdrawal will often flip, and be used as “proof” that they aren’t accepted by friends and family.

Most upsetting, DS’s are often reluctant to seek help. They may deny they are depressed, and accuse their NDS as using it as an “excuse” to attack them further. They may refuse counseling, reject psychotropic drugs, and be unwilling, or unable, to implement the very regimes that might alleviate their symptoms.

Big Pharm

There was a time when I believed that antidepressants were an evil plot by Big Pharm and to be avoided. I don’t believe that anymore. The right antidepressant not only lifts the depression, but stops the deterioration of the physical structures of the hippocampus, so I say, start them when a clinical depression settles in, and see if they help. But older antidepressants are just as effective (or more so) than newer ones. We’ve made slow progress on that front, according to Peter Kramer.

The best combo is psychotherapy and drugs, because psychotherapy increases self-awareness of the negative thought patterns, allows each spouse to voice their feelings and issues, and provides support and encouragement to the depressed person in adopting new coping skills.

Peak Shrink’s Depression

In my case, the onset of winter brings on my depression.

I don’t mean the metaphorical “winter” but the real one. It isn’t the “winter blahs,” or “cabin fever” that so many of you can relate to. It’s a condition that develops as daylight shortens, and the symptoms fade away when sunshine returns, and days are long and warm. Hypersomnia is one symptom. That’s when you sleep 10 or more hours a day, if you can, and you still don’t feel rested. There are others, like lethargy, increased appetite with weight gain (great), and irritability.

I won’t go on with a symptom list. It is depressing to talk about depression.

The best thing you can learn from struggling with depression is how to avoid it.

I first noticed it in graduate school, when I increasingly dreaded having to get up to go to a practicum I loved. My mind was at odds with itself. Why was I saying “I don’t want to go!” when I really did? I’ve since learned to disregard that voice.

The Voice

All depressed people know about “the voice.” It is that endless drone that reminds you of every mistake you ever made. Even the stupid or meaningless ones. I’ve found myself beating myself up about an embarrassing incident that happened ten years ago. Fortunately, I can catch myself doing it now and consciously break the litany by saying “It doesn’t matter. That was a long time ago.”

But the “voice” is relentless, and “stinkin’ thinkin’” a constant companion.

This winter, I was certain I was about to be fired from my job for reasons that were exceptionally trivial. But I was still convinced the likelihood was high. I forced myself to talk about it with my boss. The belief lost its grip after that.

S.A.D.

My mood disorder, called Seasonal Affective Disorder (S.A.D. for short) happens in the fall, and lifts in the spring. It can lift magically within 24 hours of being in a sunny state like Florida. I know, because it happened.

Not putting on my best “thinking cap,” I delayed beginning my psychotropic medication on my lecture tour, until my return, thinking “Cascadia is warmer, so it will be sunnier as well!”

Every year I face the same reluctance to go back on medication. Every year I keep hoping that I’ve somehow “outgrown” or “recovered” from this condition. I arrived back East smack in the middle of the shortened days and long nights. It takes 4-6 weeks for many antidepressants to work, so I had plenty of time to have a full dose of stinkin’ thinkin’ by the time it started to work. And it did. Relations were calm, work went smoothly. My next psychiatric appointment, he upped the meds, because despite a stable mood, I was still sleeping a great deal.

The Crash

Then, for reasons that I won’t go into (some stupidity shouldn’t be shared…) I decided to be my own psychiatrista while later, and tamper with my medication, which I did.

DH asked me whether the mood shift comes on me suddenly or insidiously, and I would say “both.” The blow-up is sudden, but the build-up is slow and steady pressure cooker. I can honestly say that my clinical, supervisory, and teaching work remained solid, maybe even more so as I had more empathy for the sadness and pain I see every day, but my DH and my writing took the full brunt of it.

The recognition that I had been overtaken by the Devious Crippler was a horrific fight where, the best thing I could say about it was “I didn’t throw the glass.” I credit the low-dose of meds I was still taking (!) I increased the dosage immediately after that fight. That was three weeks ago, and while I’m still not 100%, I’m much closer to normal. (Just don’t ask DH...)

I’ve found myself withdrawing from my friends, from social activities, while convincing myself that THEY didn’t want ME. This is also common with depression. You can’t push yourself to socialize, and not socializing leaves you feeling dejected and rejected.

It only makes sense when you’re depressed.

Romancing Depression

A friend of mine said one should learn to “embrace” depression. While I know we’ve come to a period in history where everyone “embraces” diseases like cancer and lupus, and even become heroes as they fight valiantly against them, let me state for the record again, there is no “soul deepening” or “spiritual uplifting” in depression. Depressed people aren’t more “creative,” and what some call “distance and objectivity” from one’s culture, I call social withdrawal. On the other side, some will argue that depression is a moral weakness, and one should “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” and “get on with it.” Both the romantic view of depression (described by Kramer as “What if Van Gogh took Prozac?”) and the reactionary “soft willed” perspective both serve no function other than to interfere with a depressed person seeking treatment.

On the continuum of MDD, mine relatively mild, and abates in the spring and summer, and for that I am grateful.

I’m familiar with the literature that says that depressed people perceive reality more accurately, and to that I would say “reality isn’t all that it is cracked up to be.”

Depression isn’t sadness, and it isn’t a “normal Doomer state.”

What’s more, when a damaged hippocampus interferes with one’s capacity to see the positive, give me a functional hippocampus, and keep your “more accurate worldview.”

I’m going to stop here for today, but I’ll leave you with one final thought:

There will come a time when admitting to a clinical depression will be no more shameful than admitting to high blood pressure or angina. Until that day comes, fellow Doomers, remember:

Just because you know that TEOTWAWKI is near, doesn’t mean you AREN’T clinically depressed.

************

Next Post: What tools are used to measure depression, and can a Doomer be labeled as having a Major Depressive Episode when they aren’t?

*To listen to another psychologist talk about her personal experience with Bipolar Disorder, go here.

**Rallying for local high schools to start later will also boost academic performance, sometimes dramatically, according to the research. Also, kids that get less than 8 hours of sleep have a 300% increased rate for obesity!

Leave a Reply