by Tanada » Thu 28 Nov 2019, 18:08:19

by Tanada » Thu 28 Nov 2019, 18:08:19

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('diemos', 'I') wish Gail the Actuary was still around to make us a graph of global per capita oil consumption.

She still posts regularly, she just doesn't bother posting here because the traffic level has shrunk so much. More of article at link below quoted section.

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('Gail Tverberg', '[')b]

Understanding Why the Green New Deal Won’t Really WorkThe reasons why the Green New Deal won’t really work are fairly subtle. A person really has to look into the details to see what goes wrong. In this post, I try to explain at least a few of the issues involved.

[1] None of the new renewables can easily be relied upon to produce enough energy in winter.

The world’s energy needs vary, depending on location. In locations near the poles, there will be a significant need for light and heat during the winter months. Energy needs will be relatively more equal throughout the year near the equator.

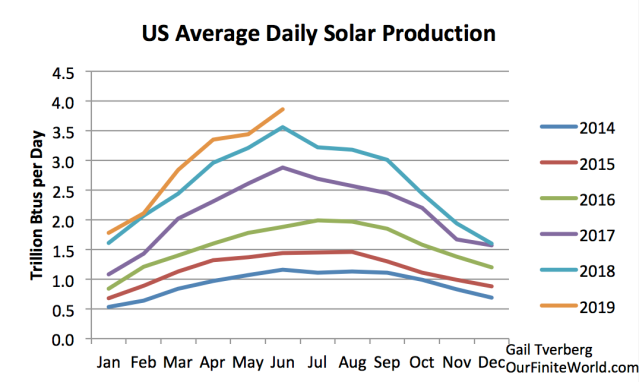

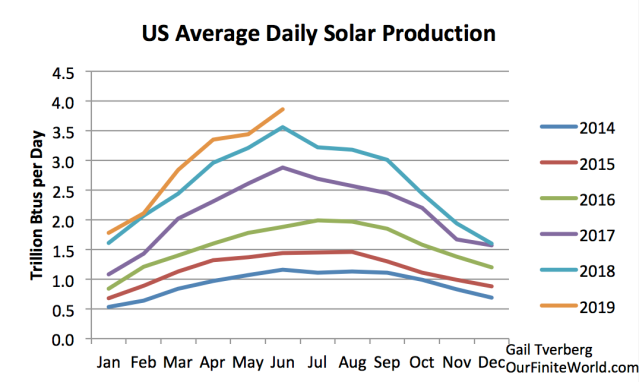

Solar energy is particularly a problem in winter. In northern latitudes, if utilities want to use solar energy to provide electricity in winter, they will likely need to build several times the amount of solar generation capacity required for summer to have enough electricity available for winter.

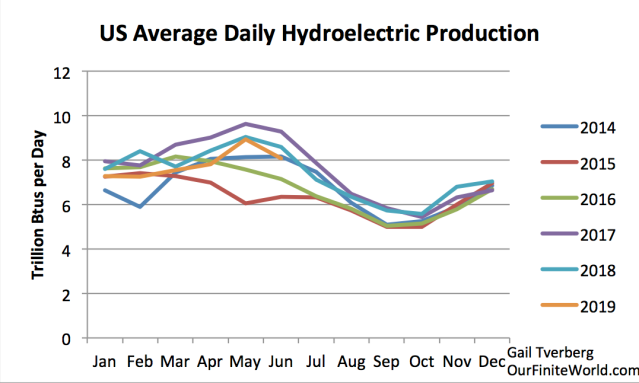

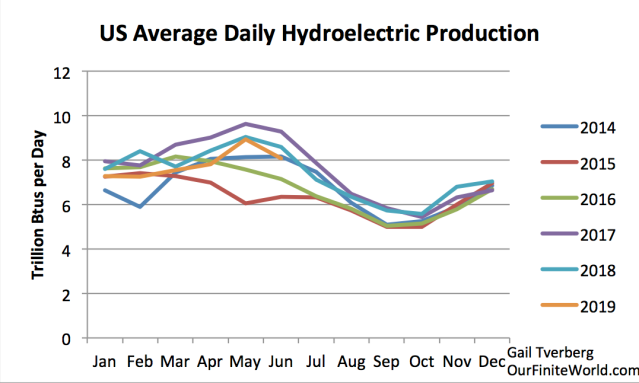

Hydroelectric tends to be a spring-dominated resource. Its quantity tends to vary significantly from year to year, making it difficult to count on.

Another issue with hydroelectric is the fact that most suitable locations have already been developed. Even if additional hydroelectric might help with winter energy needs, adding more hydroelectric is often not an option.

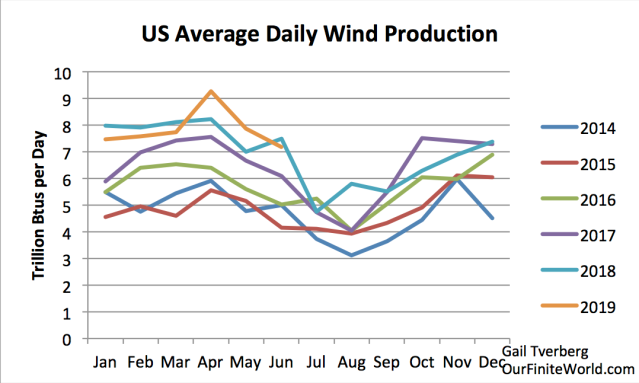

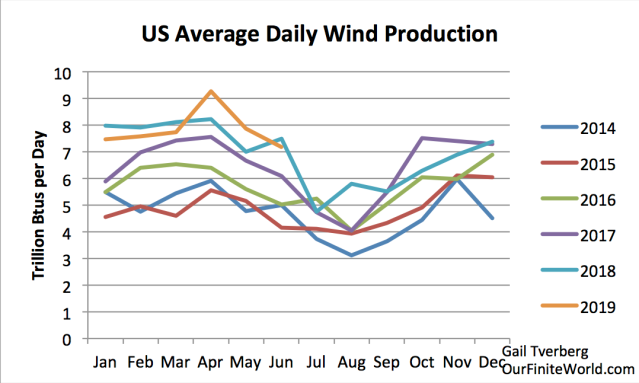

Wind energy (Figure 3) comes closest to being suitable for matching the winter consumption needs of the economy. In at least some parts of the world, wind energy seems to continue at a reasonable level during winter.

Unfortunately, wind tends to be quite variable from year to year and month to month. This makes it difficult to rely on without considerable overbuilding.

Wind energy is also very dependent upon the continuation of our current economy. With many moving parts, wind turbines need frequent replacement of parts. These parts need to be precisely correct, with virtually no tolerance for change. Sometimes, helicopters are needed to install the new parts. Because of the need for continued high-technology maintenance services, wind energy cannot be expected to continue to operate for very long unless the world economy, with all of its globalization, can continue pretty much as today.

[2] Depending upon burned biomass in winter is an option, but we already know that this path is likely to lead to massive deforestation.

Historically, people burned wood and other biomass to provide heat and light in winter. If biomass is burned for heat and light, it is an easy step to using charcoal for smelting metals for goods such as nails and shovels. But with today’s population of 7.7 billion people, the huge demand for biomass would quickly deforest the whole world. There is already a problem with growing deforestation, especially in tropical areas.

It is my understanding that the Green New Deal is focusing primarily on wind, hydroelectric, and solar rather than biomass, because of these issues.

[3] Battery backup for renewables is very expensive. Because of their high cost, batteries tend to be used only for very short time periods. At a 3-day storage level, batteries do nothing to smooth out season-to-season and year-to-year variation.

The cost of batteries is not simply their purchase price. There seem to be several related costs associated with the use of batteries:

The initial cost of the batteries

The cost of replacements, because batteries are typically not very long-lived compared to, say, solar panels

The cost of recycling the battery components rather than simply leaving the batteries to pollute the nearby surroundings

The loss of electric charge that occurs as the battery sits idle for a period of time and the loss related to electricity storage and retrieval

We can get some idea of the cost of batteries from an analysis by Roger Andrews of a Tesla/Solar City system installed on the island of Ta’u. The island is in American Samoa, near the equator. This island received a grant that was used to add solar panels, plus 3-day battery backup, to provide electricity for the tiny island. Any outages longer than the battery capacity would continue to be handled by a diesel generator. The goal was to reduce the quantity of diesel used, not to eliminate its use completely.

Based on Andrews’ analysis, adding a 3-day battery backup more than doubled the cost of the PV-alone system. (It added 1.6 times as much as the cost of the installed PV.) The catch, as I pointed out above, is that the cost doesn’t stop with purchasing the initial batteries. At least one set of replacement batteries is likely to be needed during the lifetime of the system. And there are other costs that are more subtle and difficult to evaluate.

Furthermore, this analysis was for a solar system. There seems to be more variation over longer periods for wind. It is not clear that the relative amount of batteries would be enough for 3-day backup of a wind system, or for a combination of wind, hydroelectric and solar. The long-term cost of a solar panel plus battery system might easily come to four times the cost of a wind or solar system alone.

There is also the issue of necessary overbuilding to make the system work. On Ta’u, near the equator, with diesel power backup, the system is set up in such a way that 40% of the solar generation is in excess of the island’s day-to-day electricity consumption. This constitutes another cost of the system, over and above the cost of the 3-day battery backup.

If we also eliminate the diesel backup, then we start adding more costs because the level of overbuilding would need to be even higher. And, if we were to create a similar system in a location with substantial seasonal temperature variation, even more overbuilding would be required if enough capacity is to be made available to provide sufficient generation in winter.

[4] Even in sunny, warm California, it appears that substantial excess capacity needs to be added to avoid the problem of inadequate generation during the winter months, if the electrical system used is based on wind, hydroelectric, solar, and a 3-day backup battery.

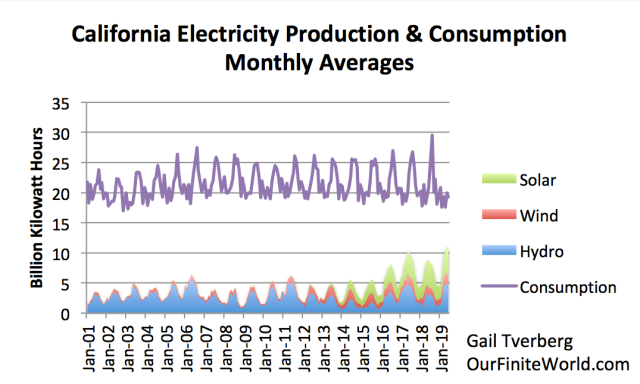

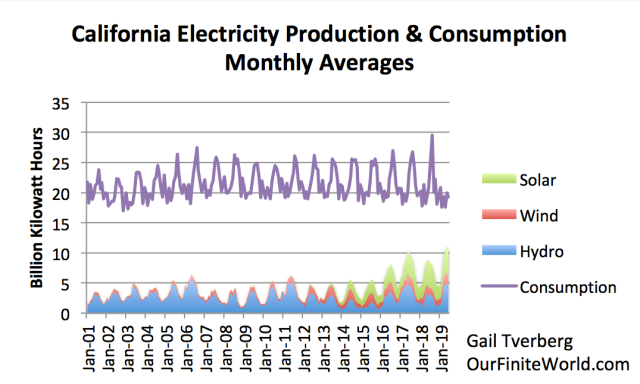

Suppose that we want to replace California’s electricity consumption (excluding other energy, including oil products) with a new system using wind, hydro, solar, and 3-day battery backup. Current California renewable generation, compared to current consumption, is as shown on Figure 4, based on EIA data.

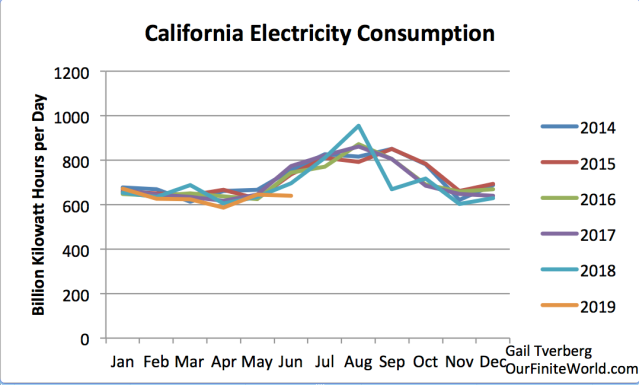

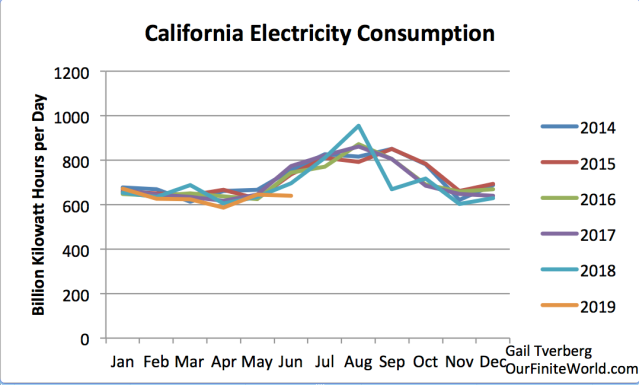

California’s electricity consumption peaks about August, presumably due to all of its air conditioning usage (Figure 5). This is two months after the June peak in the output of solar panels. Also, electricity usage doesn’t drop back nearly as much during winter as solar production does. (Compare Figures 1 and 5.)

We note from Figure 4 that California hydroelectric production is extremely variable. It appears that hydroelectric generation can vary by a factor of five comparing high years to low years. California hydroelectric generation uses all available rivers, so any new energy generation will need to come from wind and solar.

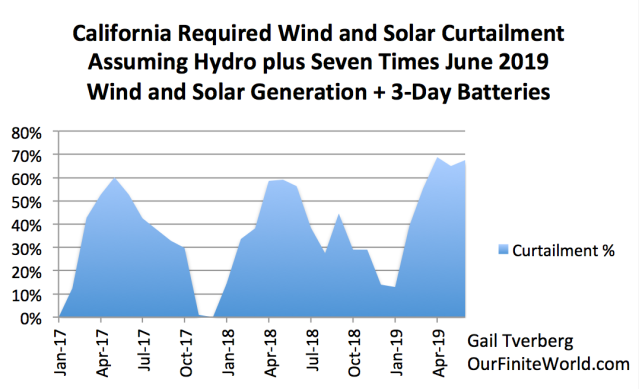

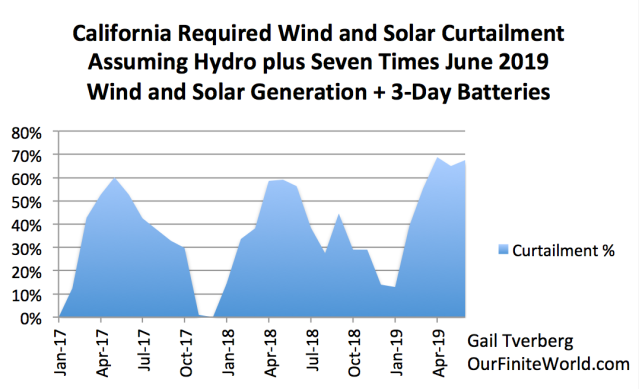

Even with 3-day backup batteries, we need the system to reliably produce enough electricity that it can meet the average electricity generation needs of each separate month. I did a rough estimate of how much wind and solar the system would need to add to bring total generation sufficiently high so as to prevent electricity problems during the winter. In making the analysis, I assumed that the proportion of added wind and solar would be similar to their relative proportions on June 30, 2019.

My analysis suggests that to reliably bridge the gap between production and consumption (see Figure 4), approximately six times as much wind and solar would need to be added (making 7 = 6 +1 times as much generation in total), as was in place on June 30 , 2019. With this arrangement, there would be a huge amount of wind and solar whose production would need to be curtailed during the summer months.

[5] None of the researchers studying the usefulness of wind and solar have understood the need for overbuilding, or alternatively, paying backup electricity providers adequately for their services. Instead, they have assumed that the only costs involved relate to the devices themselves, plus the inverters. This approach makes wind and intermittent solar appear far more helpful than they really are.

Wind and solar have been operating in almost a fantasy world. They have been given the subsidy of “going first.” If we change to a renewables-only system, this subsidy of going first disappears. Instead, the system needs to be hugely overbuilt to provide the 24/7/365 generation that backup electricity providers have made possible with either no compensation at all, or with far too little compensation. (This lack of adequate compensation for backup providers is causing problems for the current system, but it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss them here.)

Analysts have not understood that there are substantial costs that are not being reimbursed today, which allow wind and solar to have the subsidy of going first. For example, if natural gas is to be used as backup during winter, there will still need to be underground storage allowing natural gas to be stored for use in winter. There will also need to be pipelines that are not used much of the year. Workers will need to be paid year around if they are to continue to specialize in natural gas work. Annual costs of the natural gas system will not be greatly reduced simply because wind, hydro, and water can replace natural gas usage most months of the year.

Analysts of many types have issued reports indicating that wind and solar have “positive net energy” or other favorable characteristics. These favorable analyses would disappear if either (a) the necessary overbuilding of the system or (b) the real cost of backup services were properly recognized. This problem pervades studies of many types, including Levelized Cost of Energy studies, Energy Returned on Energy Invested studies, and Life Cycle Analyses.

This strange but necessary overbuilding situation also has implications for how much homeowners should be paid for their rooftop solar electricity. Once it is clear that only a small fraction of the electricity provided by the solar panels will actually be used (because it comes in the summer, and the system has been overbuilt in order to produce enough generation in winter), then payments to homeowners for electricity generated by rooftop systems will need to decrease dramatically.

A question arises regarding what to do with all of the electricity production that is in excess of the needs of customers. Many people would suggest using this excess electricity to make liquid fuels. The catch with this approach is that the liquid fuel needs to be very inexpensive to be affordable by consumers. We cannot expect consumers to be able to afford higher prices than they are currently paying for fossil fuel products. Also, the new liquid fuels ideally should power current devices. If consumers need to purchase new devices in order to utilize the new fuels, this further reduces the affordability of a planned changeover to a new fuel.

Alternatively, owners of solar panels might be encouraged to use the summer overproduction themselves. They might set the temperatures of their air conditioners to a lower setting or heat a swimming pool. It is unlikely that the excess could be profitably sold to nearby utilities because they are likely encounter the same problem in summer, if they are using a similar generation mix.

[6] As appealing as an all-electric economy would seem to be, the transition to such an economy can be expected to take 150 years, based on the speed of the transition since 1985.

Clearly, the economy uses a lot of energy products that are not electricity. We are familiar with oil products burned in many vehicles, for example. Oil is also used in many ways that do not require burning (for example, lubricating oils and asphalt). Natural gas and propane are used to heat homes and cook food, among other uses. Coal is sometimes burned in making pig iron and cement in China.

Electricity’s share of total energy consumption has gradually been rising (Figure 7).* We can make a rough estimate of how quickly the changeover has been taking place since 1985. For the world as a whole, electricity consumption amounted to 43.4% of energy consumption in 2018, rising from 31.2% in 1985. On average, the increase has been 0.37%, over the 33-year period shown. If we assume this same linear growth pattern holds going forward, it will take 153 years (until 2171) until the world economy can operate using only electricity. This is not a quick change!

[7] While moving away from fossil fuels sounds appealing, pretty much everything in today’s economy is made and transported to its final destination using fossil fuels. If a misstep takes place and leaves the world with too little total energy consumption, the world could be left without an operating financial system and with way too little food.

Over 80% of today’s energy consumption is from fossil fuels. In fact, the other types of energy shown on Figure 8 would not be possible without the use of fossil fuels.