by Graeme » Sat 06 Sep 2014, 01:32:19

by Graeme » Sat 06 Sep 2014, 01:32:19

Pops, Thanks. It's certainly worth while putting US LTO production in a global context. Looking further down in same article, I saw this:

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('', 'D')r. Miller is co-editor of a special edition of the prestigious journal, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, published this month on the future of oil supply. In an introductory paper co-authored with Dr. Steve R. Sorrel, co-director of the Sussex Energy Group at the University of Sussex in Brighton, they argue that among oil industry experts "there is a growing consensus that the era of cheap oil has passed and that we are entering a new and very different phase." They endorse the conservative conclusions of an extensive earlier study by the government-funded UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC):

"... a sustained decline in global conventional production appears probable before 2030 and there is significant risk of this beginning before 2020... on current evidence the inclusion of tight oil [shale oil] resources appears unlikely to significantly affect this conclusion, partly because the resource base appears relatively modest."

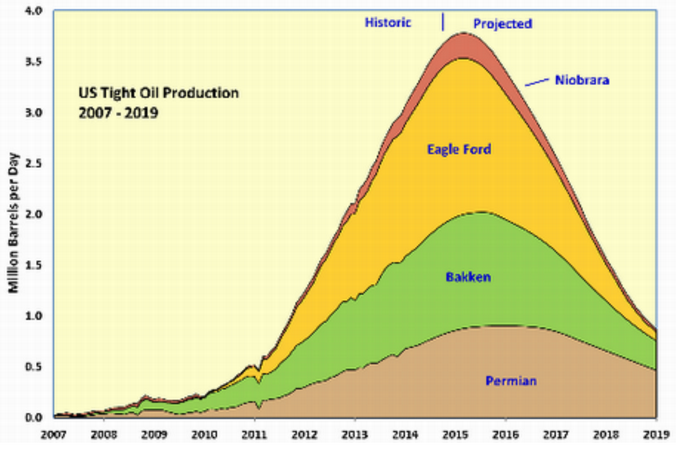

In fact, increasing dependence on shale could worsen decline rates in the long run:

"Greater reliance upon tight oil resources produced using hydraulic fracturing will exacerbate any rising trend in global average decline rates, since these wells have no plateau and decline extremely fast - for example, by 90% or more in the first 5 years."

I looked around for further info and found this on the

ASPO site which may be of interest to our community:

$this->bbcode_second_pass_quote('', 'D')epletion rates after the peak can vary widely, from about 2% per year for a well-managed onshore field, to 20% or more per year for deepwater fields like Mexico’s Cantarell field, and other deepwater fields in the Gulf of Mexico. Of the 42 largest oil producing countries in the world, representing roughly 98% of all oil production, 30 have either plateaued or passed their peaks.

Anyone familiar with a balance sheet should understand this concept, but many observers routinely miss it. World oil production must first struggle against a background decline rate of about 4.5% from mature fields before it can manage any increases. In recent years, the net increase in global oil production is about 1% per year, but we expect that to fall to zero and then go negative by 2015.

The IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2008 included, for the first time, a study of the depletion rates of the world’s top 800 oil fields. It found rates of 6.7% for past-peak fields, increasing to 8.6% by 2030 (the end date of the report’s “reference scenario”). Averaged across all fields, the rate is 5.1%. Against such high decline rates-up from a generally accepted 4.5% estimate only a few years ago–the agency calculates that the world would need to add a whopping 64 million barrels per day (mbpd) of new capacitybetween 2007 and 2030 in order to meet an anticipated demand growing at 1.6% per year. That’s like adding six new Saudi Arabias.

The IEA concluded that the world will have a hard time reaching 100 mbpd within the next two decades. Their projected supply curves are now sharply reduced, while their global demand projections continue to show about a 1.5% annual rate of growth.