Page added on July 26, 2018

Heinberg: Human Predators, Human Prey

Society as Ecosystem in a Time of Collapse, Part I

This month’s MuseLetter is Part I of a 3-part essay that uses predation as a metaphor to unpack power relations in human societies. Stay tuned!

Introduction

A lion runs down a gazelle; a raiding band brandishing clubs, bows, and arrows descends on a tribal village; a loan shark confronts a delinquent borrower.

In each of these three scenarios one party seeks to gain at the expense of the other. Without a moment’s hesitation, we classify the first interaction, between the lion and gazelle, as a predator-prey relationship. Biologists and ecologists have studied such relationships in detail for many decades, codifying principles that help us understand and predict the behavior of entire ecosystems. Could we use predator-prey relationships among widely divergent species in nature as a metaphor to help in understanding the behavior of people in complex human societies, in which some people gain at the expense of others? Even the best metaphors have limited usefulness, and this one certainly has potential for misapplication; however, as I hope to show, it also has the ability to illuminate.

A complex or stratified human society can be thought of as an ecosystem. Within it, humans (all a single species), because of their differing social classes, roles, and occupations, can act, in effect, as different species. To the extent that some exploit others, we could say that some act as “predators,” others as “prey.” There may even be human analogues to subcategories of predatory behavior such as parasitism and infection.

Within non-human species in nature, forms of competition or exploitation unquestionably exist. For example when a shoebill gives birth to two chicks, the mother and father tend to favor one of them; then the favored offspring attacks the unfavored, which inevitably dies. Bull elk battle one another for mating privileges, sometimes to the death. But the extent and variety of human ways of exploiting other humans defy comparison with the behavior of any other animal; hence the “predation” metaphor.

Human groups have “preyed” upon one another via two main pathways—intragroup and intergroup—which have often intersected or run parallel. Members of a complex society can “prey” upon other members of the same society via slavery (including sex slavery and debt slavery), caste, class, taxes, rents, crime, and debt; on the other hand, one society can “prey” upon a different society through raid, invasion, plunder, conquest, colonization, or (again) debt. In addition, members of conquered “prey” societies can be enslaved by or absorbed into the “predator” society, becoming a permanent underclass.

Speaking informally of human economic exploitation of other humans in terms of “predation” is hardly new, as we will see; however, a cursory search of the literature turned up few systematic explorations of the metaphor. In discussing the phenomenon of “predation,” I’m not so much interested in cases in which some humans actually eat others (though this did happen in some societies), but rather in forms of economic exploitation. In order to emphasize the metaphoric nature of this usage, I’ll use quotation marks in every instance where terms like predator or prey are being applied to relations among and between humans.

My main objective here is to use the “predator-prey” frame to see whether we can gain some insight into society, especially in its current context. This is not a static context; instead, it is a highly dynamic and perilous situation dominated by our society’s collision with ecological limits to further growth, including climate change, resource depletion, and species extinctions. We urgently need to understand this context better, so as to predict (at least in broad strokes) where our social “ecosystem” may be headed; to change course, in instances where there is still time to avert severe harm; and to better adapt to whatever impacts are already inevitable.

Of course, all metaphors have limited usefulness. A metaphor that classifies human beings in terms of behaviors similar to those of other animals must come with special caveats. Here are seven that I can think of:

- Seeing human social roles in terms of “predator-prey” relationships should not be interpreted as assigning superiority or inferiority. In nature, one can’t say that any species is superior or inferior to another on the basis of its ecological function. Hares are as important to the web of life as foxes. Nevertheless, as we’ll see in a later section of this essay, some “predator” humans have created belief systems (notably racism) based on the notion of superiority in order to support and maintain exploitative relationships. These belief systems have no objective basis other than their functional usefulness to “predators.” In fact, seeing these belief systems for what they are—efforts to justify exploitation—is an essential way to reduce their power.

- As human bystanders, we may admire an animal predator (such as a wolf), and may sympathize with a prey animal (such as a deer). But, taking a larger and more dispassionate view (i.e., the view of a biologist), we understand that both wolf and deer are integral to the balanced working of the larger ecosystem. In human society, however, that neutral stance must inevitably confront morality. That’s because “predator-prey” relationships among humans are, again, not biologically based; they are socially constructed. Therefore they are inevitably, and always have been, subject to negotiation, moral judgment, resistance, and rebellion.

- Human society currently is so complex that it may be hard to know who is “predator” and who is “prey” in any given situation. In all likelihood, most people simultaneously serve both functions in different aspects of their lives. Rather than attempting to throw specific people, groups, or occupations into mental bins, it is more useful for our purposes here to identify general systemic means of exploitation. Who profits from whom, and how?

- All differences in roles and power among humans may not be reducible metaphorically to win-lose “predation.” Among animals, there are many species in which individuals assume differing social roles. In a wolf pack, roles range from the alpha (the dominant leader) through the beta, selsa, delta, gamma, and so on, down to omega wolves—those who are troublesome and show little respect, and are in effect social outcasts. The “predator-prey” metaphor does little to elucidate the nature of such social roles. Even more rigid hierarchies exist among the social insects—primarily termites, ants, and bees—which have used social complexity as a spectacularly successful strategy for increasing overall competitive success vis-à-vis other species. It is therefore likely that at least some human behaviors that appear “predatory” have evolved to the advantage of the entire species. We will revisit this point repeatedly.

- Relatedly, some readers might object to the metaphor of “predation” because it is inherently violent, “red in tooth and claw” to use Tennyson’s phrase, while human society is for the most part based on cooperation and collaboration. An alternative metaphor might be just as useful: the human body with its organs and functions (brain, heart, skin, etc.). This cooperative metaphor, in which each part benefits by being integral to a larger whole, is a helpful counterbalance to the predator-prey metaphor, which is inherently conflict-based. In this essay I intend to explore human “predator-prey” relationships as a way of helping us see and understand exploitative activity in the present, but a more cooperative metaphor could be useful in understanding how social stratification and complexity evolved, and may also be helpful in imagining how human society could continue to evolve in the future.

- Apart from these caveats, there is the need for some clarification of how we’ll use the metaphor, and how we won’t. While the term “sexual predator” is in common usage, the very real phenomenon of sexual “predation” is only tangential to our subject matter—i.e., economic exploitation. Also, warfare is an obvious and important subject area in which the application of the “predator-prey” metaphor might yield insights. However, a full treatment of either sexual “predation” or warfare would make this already-long essay ungainly. I’ll touch upon both subjects briefly as needed.

- It is important to acknowledge that humans have been predators or scavengers throughout our evolutionary history, in that we are animals that eat other animals (we are, in fact, omnivores—see below). But as we humans have come to harvest more and more of Earth’s productivity, we have become, in effect, “super-predators.” We’ll seek to gain some insight into how and why that has happened in section 4.

That’s a lot of hedging. Forgive me; it really is required. Metaphors are powerful. They can help us think, but they can also prevent us from thinking. My purpose in this essay is to stretch our understanding, not to corral us into a mental cul-de-sac. Therefore it’s important to assess where and how the metaphor brings light and understanding, and where it doesn’t.

With so many potential pitfalls, why use the metaphor at all? We think in metaphors; always have, always will. Society is a system, so we need to use systems thinking to understand it. Perhaps the most studied example of a system is the ecosystem, and ecosystems are characterized by predator-prey relationships. At the same time, society is rife with exploitative relationships and behaviors that are frequently characterized as predatory. It all adds up to a compelling line of inquiry. So, even though there may be snags along the way, let’s see if we can use these observations metaphorically to probe human society at this time of great peril in order to gain some relevant insights.

2. Predator-prey relationships in nature

Predator-prey relationships are the result of hundreds of millions of years of evolution and form the warp and weft of the food web. Predators often evolve to have sharp teeth and talons while prey species typically evolve features and behaviors that enable them to escape or hide. The details of adaptation and specialization are wondrous and multitudinous.

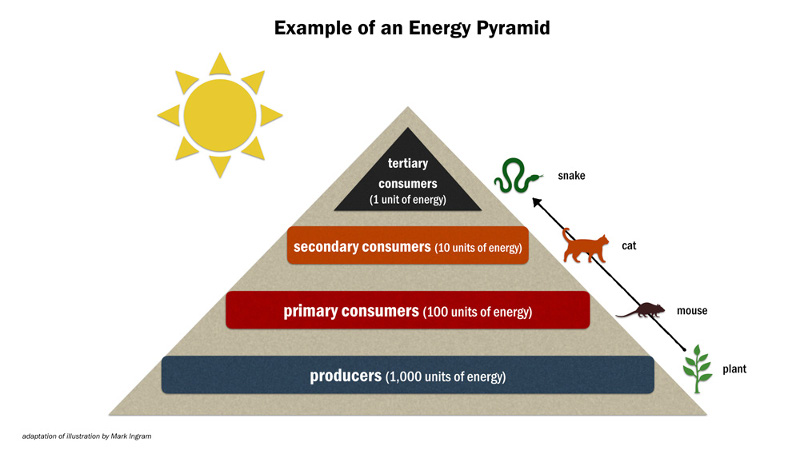

These relationships are an important means by which energy moves through the biosphere. The food web has three main elements:

- Producers, or autotrophs (plants and algae) are organisms that use energy from sunlight along with elements from air, soil, rain, or ocean to build their energy-storing tissues.

- The category of consumers, or heterotrophs (organisms that consume other organisms), consists of animals that eat primary producers, called herbivores; animals that eat other animals, called carnivores; and animals that eat both plants and other animals, called omnivores.

- Decomposers (also called detritivores) break down dead plant and animal materials and wastes and release them as energy and nutrients into the ecosystem for recycling.

The category of consumers splits further into secondary and tertiary consumers—i.e., carnivores that eat other carnivores (such as seals that eat penguins, or snakes that eat frogs that eat insects that eat other insects).

These are the trophic levels by which energy moves through an ecosystem. At each stage, most energy and materials are lost (as heat and waste) rather than being converted into work or tissues. That’s why a typical terrestrial ecosystem can support only one carnivore to ten or more herbivores of similar body mass, one secondary carnivore to every ten or more primary carnivores, and so on. (Most ocean ecosystems are characterized by an inverted food pyramid in which consumers outweigh producers; this happens because primary producers have a rapid turnover of biomass, on the order of days, while consumer biomass turns over much more slowly—a few years in the case of many fish species). If energy is a main driver of the ecosystem, it is also a main limit (along with water and nutrients).

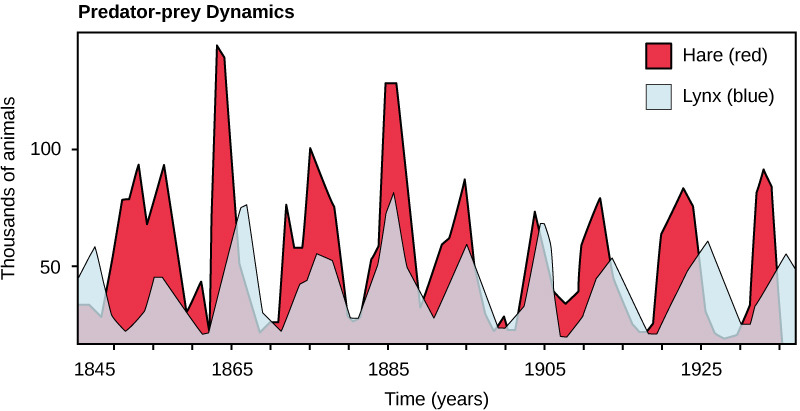

Predators keep the population levels of prey species in check, but a decline in the population of prey species (due to any cause, including over-predation) can lead to a fall in the population of predators. Typically, the abundance of prey and predators is characterized by cycles, with the population peaks of predators often lagging those of prey.

The cycling of lynx and snowshoe hare populations in Northern Ontario. Source

Let’s focus on one example—the field mouse, or vole. Its numbers in any given area vary according to the relative abundance of its food (typically small plants), which in turn depends on climate and weather. The local vole population size also depends on the numbers of its predators—which include foxes, raccoons, hawks, and snakes. A wet year can result in heavy plant growth, which temporarily increases the land’s carrying capacity for voles, allowing the vole population to grow. This growth trend is likely to overshoot the vole population level that can be sustained in succeeding years of normal rainfall; this eventually leads to a partial die-off of voles. Meanwhile, during the period that the population of voles is larger, the population of predators—say, foxes—increases to take advantage of this expanded food source and improve their odds of surviving, successfully reproducing, and raising kits. But as voles start to disappear, the increased population of predators can no longer be supported. Over time, the populations of voles and foxes can be described in terms of overshoot and die-off cycles, again tied to external factors like longer-term patterns of rainfall and temperature.

Using tools, language, and agriculture, early humans gradually found ways to overcome several key natural checks and balances. With our weapons we could kill off our predators, like lions and tigers. Now the only large-bodied direct challengers we had to worry about were other humans. We could expand into new territories. We could adapt to using new and different resources. As a result, the total human population tended to grow slowly over thousands of years (with occasional setbacks).

Still there were limiting factors, one of which was energy. As long as we depended on firewood for fuel, our numbers were partly limited by the availability of trees. Ancient civilizations consumed forest after forest—indeed, one of the oldest known human stories, the Epic of Gilgamesh, revolves around the hero chopping down trees—and the resulting deforestation was sometimes associated with the decline of civilizations. But in the last few centuries, and especially the last decades, fossil fuels began to substitute for firewood. This substitution enabled a massive increase in the global human population (as we’ll discuss in a bit more detail in section 4).

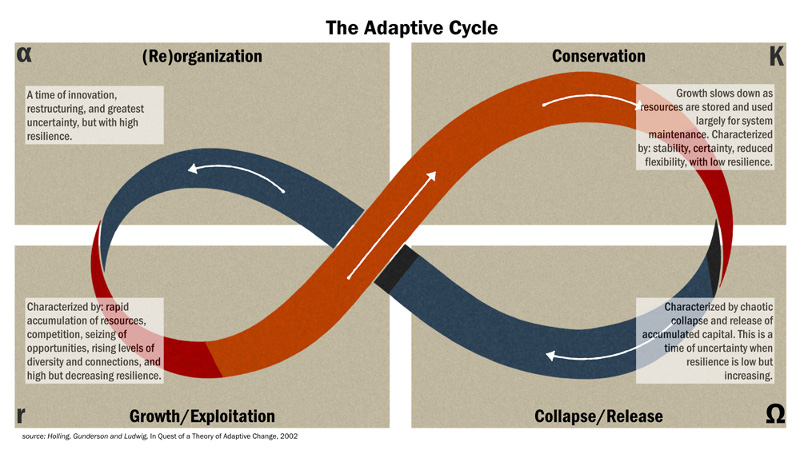

Predator-prey relationships make ecosystems dynamic and complex. Efforts to understand that dynamism and complexity have led to the development of resilience science, and to a key concept known as the adaptive cycle; this describes the cycle of resource organization, growth (or exploitation), conservation, and release that ecosystems have been observed to follow. For example, in a Ponderosa pine forest the collective behavior of plants and animals organizes itself in a predictable pattern. First, following a disturbance, hardy and adaptable “pioneer” species of plants and small animals fill open niches and reproduce rapidly. Over time, those species that can take advantage of relationships with other species start to dominate. These relationships make the system more stable, but at the expense of diversity. Resources like nutrients, water, and light are so taken up by the dominant species that the system as a whole loses its flexibility to deal with changing conditions. Finally, these trends accumulate to make the system susceptible to a crash—say, a wildfire. Many trees die, releasing their nutrients, opening the forest canopy to let more light in, and providing habitat for shrubs and small animals—and the cycle starts over.

Some resilience scientists have observed that the adaptive cycle also characterizes the evolution of human societies, which likewise go through periods of growth, conservation, release, and reorganization. Ancient China, for example, saw several such cycles. Throughout the remainder of this essay I will be discussing the adaptive cycle primarily as it relates to human society, and especially to the current status of global industrial society.

3. The origin and development of the human “predator-prey” relationship

The exact process that led to social stratification (class-based variance in social power and wealth) and complexity (a term that reflects the number and variety of technologies, social roles, and institutions in a society) is still unclear after decades of research by historians, anthropologists, and archaeologists. However, some general features of this evolutionary pathway have been clear at least since the 1960s.

For tens of thousands of years, all humans subsisted by hunting and gathering. People usually lived in small groups, most of which were nomadic—though in particularly abundant regions, it was possible for settlements to persist in place. Some of these settlements were ceremonial or trading centers. Authority within groups was mostly situational, based on demonstrated knowledge and skill; anyone who felt oppressed could (in principle, at least) simply leave. Under harsh natural conditions, some groups raided other groups’ stores of food, often wounding or killing fellow humans in the process, occasionally taking captives. Revenge raids or killings would often follow. Archaeological research has shown that levels of interpersonal violence among hunter-gatherers varied greatly, but were generally very high.

Simple horticultural (i.e., gardening) societies emerged as animals and plants began to be domesticated, though a large proportion of calories still came from hunting and gathering. These societies tended to establish temporary villages; political organization often featured a “Big Man” who gained influence and prestige through demonstrations of generosity and redistribution, but who exerted no coercive authority.

Complex horticultural societies established stationary towns, a few of which were large enough to be called cities. Some production was for exchange, and trade expanded. These societies were organized around chiefs—who were hereditary and enjoyed privilege as well as influence and prestige. Among some groups, warfare became highly ritualized and valorized.

Pastoral or herding societies tended to exist in marginal environments (such as deserts); their subsistence revolved around the keeping of domesticated grazing, ruminant animals including cattle, goats, sheep, and members of the camel family. These pastoral societies, while usually migratory, again featured hereditary chiefs, were highly patriarchal, and often inclined toward warfare as a cultural organizing principle.

The advent of agricultural societies (defined by the growing of field crops) eventually brought cities and full-time division of labor. Societies became much larger, each identifying itself with a specific geographic region over which the state claimed ownership. Social stratification also appeared, sometimes in the form of a rigid, intergenerational caste system. Echoing the trophic levels in natural ecosystems, the peasant “producer” class was far more numerous than the ruling or elite class (soon there were also full-time soldiers, artisans, artists, merchants, money lenders, and so on); money, law, prisons, standing armies, and writing all appeared at this stage. At the head of the state was a divine king, whose family shared in his coercive authority as well as his privilege and prestige. This is the point at which “predation” within human society (not just between societies) appears to have become institutionalized. At the same time, however, levels of interpersonal violence (excluding warfare, i.e., inter-group violence) declined significantly.

In some instances, an agricultural society appears to have been conquered and dominated by a smaller but highly aggressive pastoral group, whose hereditary rulers then pursued the project of wider conquest (this appears to have been the case in ancient and medieval China, for example; though there were also instances where expanding agricultural states appear to have “preyed” upon peripheral pastoralists). The result then was the establishment of an empire, with a central state systematically siphoning wealth from peripheral colonies. Often people from conquered lands were imported to the capital as slaves.

This simple schema runs the risk of oversimplification; indeed, recent research has uncovered surprising exceptions at each stage along the way—including hunters and gatherers who were mostly sedentary, and early cities that were egalitarian and showed no evidence of stratification. The path of social complexification and stratification often meandered and doubled back. Nevertheless, the essential trend persisted: as people organized themselves within ever-larger groups and exploited their environments more systematically, coercive authority tended to appear—whether in central America, Europe, north Africa, south Asia, or east Asia. A relatively small elite group took charge and gained wealth and power. The masses, meanwhile, were held in a condition of relative poverty, their labor organized and controlled by overlords. All this time, the most “advanced” societies grew in complexity, power, and sophistication.

Among social scientists, there have been two schools of thought with regard to the origin of stratification and complexity; Joseph Tainter, in The Collapse of Complex Societies, summarizes these schools of thought clearly. “Conflict theory,” writes Tainter, “asserts that the state emerged out of the needs and desires of individuals and subgroups of a society. The state, in this view, is based on divided interests, on domination and exploitation, on coercion, and is primarily a stage for power struggles.” Karl Marx and his followers were prominent exponents of conflict theory. In contrast (again quoting Tainter), “Integrationist . . . theories suggest that complexity, stratification, and the state arose, not out of the ambitions of individuals or subgroups, but out of the needs of society.” Even some apparent instances of domination and exploitation, in this view, may have emerged because there was a common advantage to such arrangements. Tainter, who regards the development of complexity as a problem-solving strategy adopted by society as a whole, suggests that a synthesis of conflict and integrationist views is needed, but leans toward the integrationist position.

The most interesting recent work related to this question has come from cultural evolution theorists including Peter Turchin—who suggests that near-constant warfare was the mechanism that led from one stage of social organization to the next. The subtitle of Turchin’s 2016 book, Ultrasociety: How 10,000 Years of War Made Humans the Greatest Cooperators on Earth, encapsulates his thesis. In essence, he persuasively argues that internal complexity based on cooperation enabled societies to compete more effectively with one another under conditions of frequent bloody conflict.

In developing the predation metaphor, I have so far compared human society to a wild ecosystem. However, once humans had left hunting and gathering behind, they no longer inhabited an entirely wild ecosystem. Increasingly, they were domesticating plants and animals and altering landscapes to support domesticated species. This behavior may shed some light on the evolution of relations between humans, who were, in effect, also “domesticating” themselves and one another. Wikipedia defines domestication as “a sustained multi-generational relationship in which one group of organisms assumes a significant degree of influence over the reproduction and care of another group to secure a more predictable supply of resources from that second group.” Domesticated non-human species can be said to have benefitted from the relationship: by giving up freedom, they gained protection, a stable source of food, and the opportunity to spread their population through a wider geographic range (as Michael Pollan discusses in his popular book The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s Eye View of the World). As we’ll see, the same benefits accrued to humans themselves as they became more “domesticated.”

Several authors seem independently to have come upon an insight that’s key to our present discussion: the human domestication of prey animals, effectively a predator-organized system for the management of prey, may have served as a template that could be transferred to intra-human relations. Humans domesticating an animal species must have had to organize their own thinking and behavior in order to tame, feed, and selectively breed their animal captives. Once we domesticated prey animals, did we replicate that thinking, and those behaviors, within human society? Domestication began before, or concurrent with, the development of stratification and complexity—not after it (though the process has continued to the present). Thus it is extremely unlikely that human slavery served as a model or inspiration for animal domestication; however, the reverse is entirely possible.

A test of this hypothesis might be to examine parts of the world that didn’t have cattle, pigs, and horses and inquire if slavery still occurred in those places. However, candidate areas are problematic. Hunter-gatherer societies (e.g., aboriginal Australians) typically had no domesticated animals other than the dog, and no slavery or other systems of intra-societal exploitation; however, inter-societal raids were frequent and captives were sometimes taken. In the case of Pre-Colombian America, domesticated animals consisted primarily of dogs and turkeys in North America; and guinea pigs, llamas, and alpacas in South America. Slavery was institutionalized among at least some indigenous peoples of the Americas: many groups enslaved war captives, who were used for small-scale labor. Some captives were ritually sacrificed in ceremonies that sometimes involve ritual torture and cannibalism. Many groups permitted captives to gradually become integrated into the tribe. Slaves were not bought and sold, but could be traded or exchanged with other tribes.

The hypothesis appears difficult to test in this way. But indirect evidence supports it. Echoing the earlier work of ecologist Paul Shepard, anthropologist Tim Ingold at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, in his book The Perception of the Environment (2000), argues that foraging peoples regarded animals as their equals, while pastoralists tended to treat their domesticated animals as property to be mastered and controlled. Archaeologist Guillermo Algaze at the University of California in San Diego finds that the first city-states in Mesopotamia were built on the principle of transferring methods of control from animals to fellow humans: scribes employed the same categories to describe captives and temple workers as they used to count state-owned cattle—which were among the first forms of property and money.

Hunter-gatherers were typically difficult to “domesticate,” often preferring death to slavery (as Stanley Diamond and others have discussed). At the other end of the spectrum are modern citizens exposed in childhood to universal compulsory education—which, with its bells, routines, inculcation of behavioral norms, segregation of children by age, and ranking by achievement, results in adults prepared for life in an orderly, stratified, scheduled, and routinized society.

Predation could be said to foster its own psychology. Predators (non-human and human) do not appear to view their prey with much compassion; predation is a game to be played and enjoyed. If orcas and cougars could speak, they might echo the typical words of the professional bill collector: “It’s nothing personal; it’s just business.” The psychology of domestication follows suit: sheep, cattle, pigs, and poultry are often regarded simply as commodities, rather than as conscious beings with intention, imagination, and feeling. For a family living on a farm, daily proximity with livestock entails getting to know individual animals, a few of which may earn sympathy and respect (especially from children). Many keepers of livestock genuinely care for their animals, treating them when they are sick and making sure that, when the animals are finally killed for food, the killing occurs with minimal pain and suffering. But when any animal comes to be seen as food, empathy is often attenuated—as it is in many slaughterhouses and fishing trawlers.

Evidently domestication wasn’t always motivated by the desire for food. Some domesticates became workers (horses, oxen, mules) or pets; the latter provided affection, companionship, amusement, and beauty. In class-based societies, rulers similarly exploit worker humans, and develop close relationships with “pet” artists, musicians, and other creative people (as well as concubines and sex slaves) who likewise supply companionship, beauty, and amusement. Today, many people lavish extraordinary care on their pets (as ancient Egyptians did with their cats), while society heaps attention and riches on elite musicians, actors, artists, athletes, models, and authors.

Are human “predator-prey” relationships as essential to complex human society as animal predator-prey relationships are to healthy ecosystems? Political idealists have replied with a resounding “no,” though the evidence is somewhat debatable. Cooperative complex institutions (such as cooperative businesses) are numerous and successful. Further, some industrial societies feature much lower levels of wealth inequality than do others. Clearly, humans are able to limit “predation” in favor of cooperation, and a diverse cottage industry of scholars (working in fields such as anti-racism, cooperative economics, and non-violent communication) has grown up to help this transformation occur. This is a point to which we will return toward the end of the essay.

Nonetheless, in the world currently, inequality and “predation” remain facts of life. And the consequences are clear not just for humans, but the entire biosphere, as we are about to see. Let’s turn our attention next to the environmental stage on which the drama of “domestication” and “predation” now plays.

11 Comments on "Heinberg: Human Predators, Human Prey"

Makati1 on Thu, 26th Jul 2018 7:44 pm

The Great Leveling is underway: “America Sacrificed At The NWO Altar”

“There is a disconnect within the liberty movement over the notion of where to find the root source of globalism. A segment of people within the movement seem to think that the fount of globalism resides within America itself; that American imperialism is the foundation of the globalist scheme and the dollar is the single most important mechanism supporting their power. This is an naive oversimplification of the problem….

,,, these assumptions were based on the idea that central bankers and globalists need the U.S. economy and the dollar system in order to maintain financial control of the world in general.

All of these assumptions also turned out to be completely false…

The central bankers KNOW exactly what they are doing and what will happen as a result. They are bringing down the U.S. economy deliberately…they refused to accept was the possibility that the Fed is actually a suicide bomber whose goal is to eventually destroy itself and everything around it, thus bringing down America from within…. now the banking elites are moving on to a “new world order” in which America plays a far diminished role….

…what we are witnessing is 4th generation warfare on the public – All other wars including the trade war are kabuki theater designed to distract from this reality.”

http://www.alt-market.com/articles/3479-trump-vs-the-fed-america-sacrificed-at-the-nwo-altar

This article does a good job explaining what I mean by “The Great Leveling”.

Only the blind or stupid cannot see it happening. The Fed is part of the take down plan and the sheeple are distracted by the Kardashians or sports or which bathroom to use. LMAO Slip slidin’…

dave thompson on Thu, 26th Jul 2018 10:02 pm

Humans are destroying the base of the food chain. In the oceans, rivers, lakes and on land. Without the phytoplankton and soil microbes and all the other tiny creatures that are the base of the food chain human extinction is inevitable.

Makati1 on Thu, 26th Jul 2018 10:10 pm

dave, I’m glad to see that someone on here has some biological education. Few realize that it is the invisible-to-the-eye critters that keep us alive. The millions of live things in one cubic foot of soil.

The need for water not polluted by the tens of thousands of toxic chemicals we have devised and dumped into the rivers and oceans.

The same for the air we breathe, now polluted with all kinds of chemical fumes that are toxic to life.

WE have sealed our fate with our ignorance and greed. It is only a matter of time…

dave thompson on Thu, 26th Jul 2018 11:26 pm

Makiti1, The problem is that the food chain was part of my grammar school education. Somewhere around the age of 8 or 9. It always stuck in my head because of the idea of these little tiny creatures inhabiting the earth and humans being at the top. Humans do tend to be very dismissive. But as we destroy that base of the food chain, because it is mostly unseen in our daily lives, humans will collectively continue on to extinction.

onlooker on Fri, 27th Jul 2018 4:09 am

Capitalism by its nature is inherently about predation and exploitation. And together with the abundant energy derived from FF, our species has perfected this predator/prey relation. But exploiting the basis for your survival being the planet is NOT wise. So, insatiable greed and competitive drive for hegemony is leading ALL of us to the nadir. No winners! How ironic

Sissyfuss on Fri, 27th Jul 2018 10:02 am

We are coming to the end of growth in the Anthropocene. The entrenched systems raison d’être us growth. It cannot change, it can only be replaced. What a challenge we are facing!

Sissyfuss on Fri, 27th Jul 2018 10:06 am

Civilization and abundant FFs have kept the predator-prey dynamic in check but as things continue to deteriorate survival of the fittest will come to the fore as before.

onlooker on Fri, 27th Jul 2018 10:24 am

Sissy in another thread, I actually said that FF and our economic system ie Civilization has actually perfected the predator/prey relation. With all the groups and tiers we are divided into and with how Capitalism, FF have enabled the power of money to allow massive pervasive exploitation of many people and of the Earth

Cloggie on Fri, 27th Jul 2018 11:42 am

https://www.eurocanadian.ca/2018/07/the-fourth-turning-and-new-homeland-for-euro-canadians.html?m=1

Hey look, in Canada they have identitarians too! Welcome home to Europe folks, in a spiritual sense.

And Richard Spencer can’t be bothered about the American flag anymore. Instead he has the English and German flag:

https://twitter.com/RichardBSpencer/status/1022852015141969924

Hungry World on Fri, 27th Jul 2018 2:49 pm

This is a nice big-picture exploration of humanity. Have to admit that I always felt like I was being indoctrinated via the public school system and later by various employers with their mandatory Kool-Aid consumption.

While I see some Moderns like the some of the Nordic countries making conscious moves towards more egalitarian and healthier work-life social structures while not abandoning market-driven commerce, I fear that the stresses are piling up faster than most societies can rationally cope and that has a sad history of favoring totalitarianism.

Makati1 on Fri, 27th Jul 2018 8:34 pm

“Would any sane person choose America’s broken healthcare system over a cheaper, more effective alternative? Let’s see: the current system costs twice as much per person as the healthcare systems of our developed-world competitors, a medication to treat infantile spasms costs $8 per vial in Europe and $38,892 in the U.S., and by any broad measure, the health of the U.S. populace is declining.”

https://www.theburningplatform.com/2018/07/27/how-systems-and-nations-fail-chs/#more-180370

“s and Nations fail – CHS

https://www.oftwominds.com/blog.html

July 27, 2018

These embedded processes strip away autonomy, equating compliance with effectiveness even as the processes become increasingly counter-productive and wasteful.

Would any sane person choose America’s broken healthcare system over a cheaper, more effective alternative? Let’s see: the current system costs twice as much per person as the healthcare systems of our developed-world competitors, a medication to treat infantile spasms costs $8 per vial in Europe and $38,892 in the U.S., and by any broad measure, the health of the U.S. populace is declining.

This is how systems and nations fail: nobody chose the current broken system, but now it can’t be changed because the incentive structure locks in embedded processes that enrich self-serving insiders at the expense of the system, nation and its populace.

Nobody chose America’s insane healthcare system–it arose from a set ofinitial conditions that generated perverse incentives to do more of what’s failingand protect the processes that benefit insiders at the expense of everyone else.

In other words, the system that was intended to benefit all ends up benefitting the few at the expense of the many.

The same question can be asked of America’s broken higher education system: would any sane person choose a system that enriches insiders by indenturing students via massive student loans (i.e. forcing them to become debt serfs)?

Students and their parents certainly wouldn’t choose the current broken system, but the lenders reaping billions of dollars in profits would choose to keep it, and so would the under-assistant deans earning a cool $200K+ for “administering” some embedded process that has effectively nothing to do with actual learning.

The academic ronin a.k.a. adjuncts earning $35,000 a year (with little in the way of benefits or security) for doing much of the actual teaching wouldn’t choose the current broken system, either.

Now that the embedded processes are generating profits and wages, everyone benefitting from these processes will fight to the death to retain and expand them, even if they threaten the system with financial collapse and harm the people who the system was intended to serve.

How many student loan lenders and assistant deans resign in disgust at the parasitic system that higher education has become? The number of insiders who refuse to participate any longer is signal noise, while the number who plod along, either denying their complicity in a parasitic system of debt servitude and largely worthless diplomas (i.e. the system is failing the students it is supposedly educating at enormous expense) or rationalizing it is legion.

If I was raking in $200,000 annually from a system I knew was parasitic and counter-productive, I would find reasons to keep my head down and just “do my job,” too.

At some point, the embedded processes become so odious and burdensome that those actually providing the services start bailing out of the broken system. We’re seeing this in the number of doctors and nurses who retire early or simply quit to do something less stressful and more rewarding.

These embedded processes strip away autonomy, equating compliance with effectiveness even as the processes become increasingly counter-productive and wasteful. The typical mortgage documents package is now a half-inch thick, a stack of legal disclaimers and stipulations that no home buyer actually understands (unless they happen to be a real estate attorney).

How much value is actually added by these ever-expanding embedded processes?

By the time the teacher, professor or doctor complies with the curriculum / “standards of care”, there’s little room left for actually doing their job. But behind the scenes, armies of well-paid administrators will fight to the death to keep the processes as they are, no matter how destructive to the system as a whole.

This is how systems and the nations that depend on them fail. Meds skyrocket in price, student loans top $1 trillion, F-35 fighter aircraft are double the initial cost estimates and so on, and the insider solutions are always the same: just borrow another trillion to keep the broken system afloat for another year.”

Slip slidin’…