Page added on February 28, 2012

A Dynamic Function for EROI

The post below is a reproduction of a paper published in the open access journal Sustainability by Michael Dale, Susan Krumdieck, and Pat Bodger (Vol. 3).The article is a first in creating a dynamic function where Energy Return on Energy Investment changes of an energy resource are estimated over time. In this manner it becomes possible to get an estimate of how much net energy a given fossil oil, gas, coal or renewable energy source yields during its lifetime. The created EROI function is based on theoretical considerations of energy technology development and resource depletion.

Any errors in the version below the fold relative to the original are solely the responsibility of the TOD editorial team. The original version can be found via Dale M., Krumdieck S., Bodger P. A Dynamic Function for Energy Return on Investment. Sustainability. 2011; 3(10):1972-1985.

Table of contents

1. Introduction

1.1 Energy Analysis

1.2 Net Energy and EROI

2. A Dynamic Function for EROI

2.1 Theoretical considerations

2.2. Technological Component

2.3. Physical Depletion Component

2.4. Finding pmax

2.5 The EROI Function for Renewable Resources

3. Discussion

3.1 supporting evidence

3.2. What Use is the EROI Function?

4. Conclusions

References

Energy is fundamentally important to all of the processes that occur within our modern, (post)industrial society. It has been famously described by James Clerk-Maxwell as, “the ‘go’ of things” [1]. Modern society currently uses around 500 exajoules (1 EJ = 1018 J) of primary energy, 85% of which comes from fossil fuels. Some proportion of this 500 EJ must be used in the extraction and processing of energy resources, as well as in the manufacture of energy technology infrastructure, such as oil rigs and dams for hydroelectricity. This paper is intended as a discussion piece regarding some of the conceptual issues surrounding long-term dynamics of the energy supply system which maybe understood using the dynamic EROI function.

Energy analysis is the process of measuring the energy flows through the process or system under investigation. According to Boustead and Hancock [2], “Energy analysis is a technique for examining the way in which energy sources are harnessed to perform useful functions” Peet [3] classifies energy analysis as, “determination of the amount of primary energy, direct and indirect. that is dissipated in producing a good or service and delivering it to the market” reflecting the current focus of energy analyses on economic activities. Energy analysis is important for a number of reasons:

- Firstly, because of the adverse environmental impacts linked with energy transformation processes, especially of concern recently being the emission of greenhouse gases associated with the combustion of fossil fuels (possible solutions include carbon capture and storage (CCS), however the increased energy consumption entailed by CCS may (dis)favor certain methods of energy production);

- Secondly, because of the finite availability of fuels and other energy resources (whereas non-renewable resources are finite in terms of total quantity, renewable resources are finite in the magnitude of their flow) and;

- Thirdly, because of the strong link between net energy and the material standard of living and economic opportunity offered by a society [4].

There is evidence that the qualities (i.e., net energy returns) of the major energy sources in use by society (coal, oil and gas) are declining [5]. Ceteris paribus, a decline in EROI of energy resources will increase the environmental impacts of an energy production process. Also, since more energy must be extracted to deliver the same amount of net energy to society this will entail faster consumption of finite energy resources. A society dependent on energy resources with lower EROI must also commit relatively more energy to the process of harnessing energy, hence has less available for other economic activities.

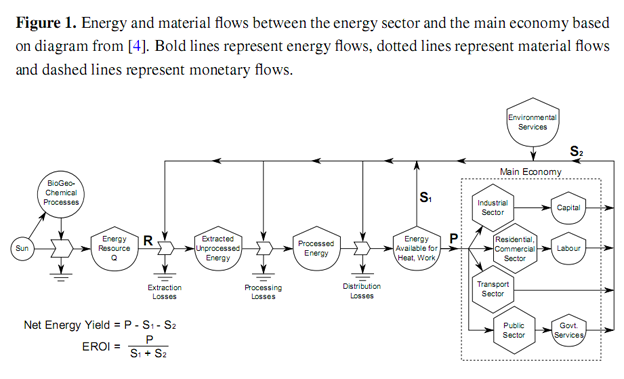

Whereas standard econometric energy models, such as MESSAGE [6], MARKAL [7] and the IEA’s World Energy Model[8], account only for gross production by the energy sector, P, net energy analysis (NEA) considers all energy flows between the energy sector and the rest of the economy, as depicted in Figure 1. The energy sector receives two inputs from the rest of the economy in order to produce energy. Inputs in the form of energy, S1 enable the energy sector to run its equipment, i.e., process energy. Inputs in the form of human-made-capital (HMC), S2, are the physical plant that must be put in place in order to extract energy from the environment, e.g., oil wells, wind turbines, hydro dams, etc.

- 1. the energy flow rate of the resource is declining, such as due to an increase in the water production of an oil field;

- 2. more energy is required to extract the resource, such as oil extraction by pumping down steam or gas during enhanced oil recovery (EOR) or;

- 3. both 1 and 2 are occurring simultaneously.

In all cases the amount of energy required to produce a unit of energy output increases. This greater energy requirement will either be made up by utilizing energy flows from within the same energy production process (internal), such as an oil producer using oil from the field to produce steam for EOR, or from energy flows originating outside of the process (external), such as an oil producer using coal or natural gas for the same purpose [10]. In the latter case, the oil production process may be competing directly with other end-uses for the energy. Many authors have begun questioning the effects that declining EROI values will have on the economy [3–5,11,12].

2. A Dynamic Function for EROI

2.1 Theoretical Considerations

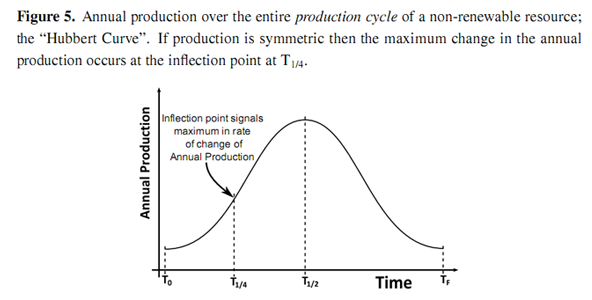

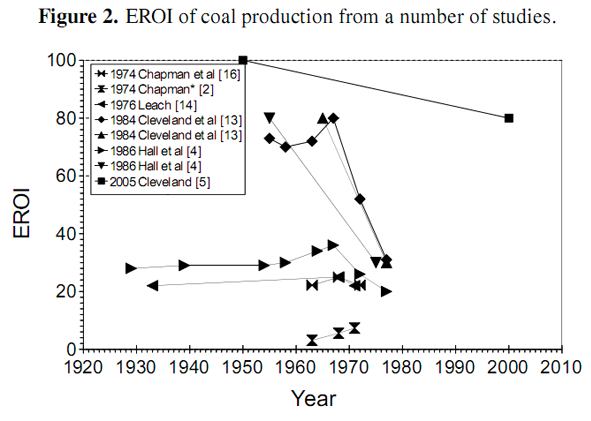

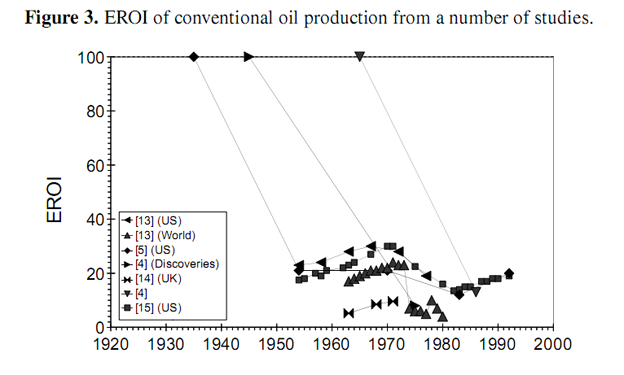

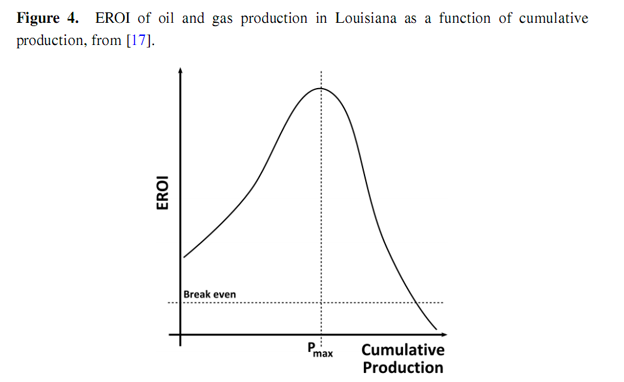

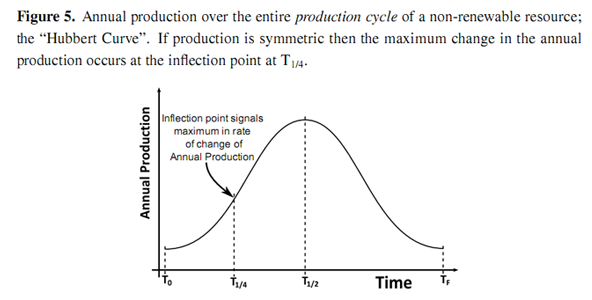

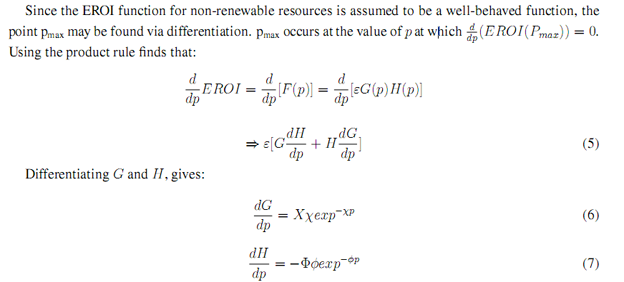

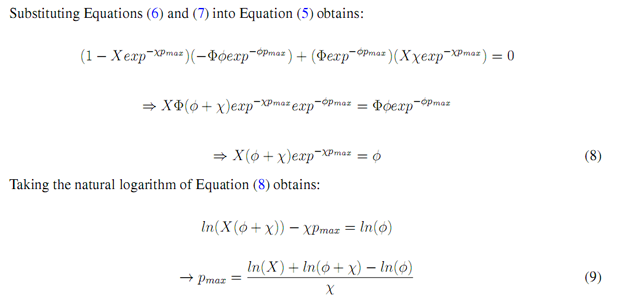

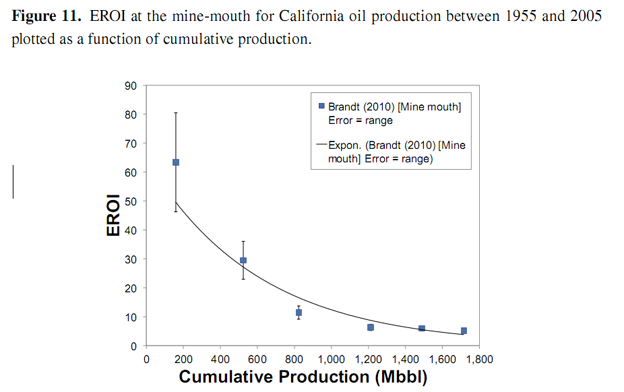

Most estimates of EROI are made as static estimates of a resource at a particular moment in time. The authors have located over 500 such estimates for all of the energy resources currently under development, as well as some still under R & D. Some dynamic estimates have been made which track the EROI of aparticular fossil resource as it changes over time. A number of such studies track the EROI of coal and oil production from various different resources over several decades [4,5,13–16], as depicted in Figures 2 and 3. The studies show that the EROI of most energy resources (coal and oil) has been either (relatively) stable at an EROI of 20–40 or decreasing over time, some from an EROI of over 100. One such study has been conducted by Costanza and Cleveland [17] of oil and gas production in Louisiana. They identify a very characteristic shape for the EROI as a function of cumulative production, as shown in Figure 4. The EROI of the resource initially increases before reaching some point of production, Pmax, at which point the energy return is at its maximum value, before declining and eventually dropping below the break-even limit represented by an EROI value of one. In this paper, we offer an explanation for the shape of this curve.

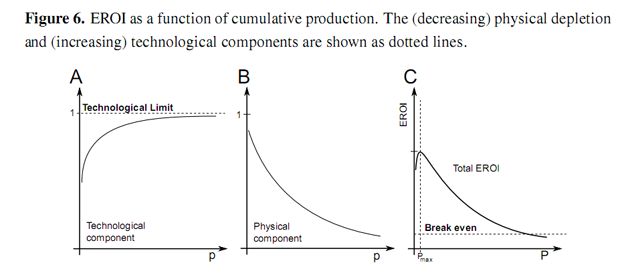

We assume that the technological component of the EROI function asymptotically increases as a function of production as shown in Figure 6. There are two factors that will influence this technological component of the EROI function: how much energy must be embodied within the equipment used to extract energy and how well that equipment performs the function of extracting energy from the nvironment. We assume that both of these factors are subject to strict physical limits. Firstly, that there is some minimum amount of energy that must be embodied in order to function as an energy extraction device, for instance the foundation of a wind turbine must successfully endure a large moment load. Secondly, there is a limit to how efficiently a device can extract energy. We further assume that, as a technology matures, i.e., as experience is gained, the processes involved become better equipped to use fewer resources: PV panels become more efficient and less energy intensive to produce; wind turbines become more efficient and increasing size allows exploitation of economies of scale. These factors serve to increase energy returns. However, it can be expected that these increases are subject to diminishing marginal returns as processes approach fundamental theoretical limits, such as the Lancaster-Betz limit in the case of wind turbines. Technological learning curves (sometimes called cost or experience curves) track the costs of production as a function of production. These often follow an exponentially declining curve asymptotically approaching some lower limit. The progress ratio specifies the production taken for costs to halve. Between 1976 and 1992, the PV module price per watt of peak power, Wp, on the world market was 82% [19]. This means that the price halved for an increase in cumulative production of 82%. Lower financial production costs should correlate with lower values of embodied energy [4,20,21]. The specific form of the function is:

Here X represents the initial value of the immature technology and (chi) χ represents the rate of technological learning through experience, which will be dependent on a number of both social and physical factors. This rate is assumed constant.

2.3. Physical Depletion Component

The physical resource component of the EROI function is assumed to decrease to an asymptotic limit as a function of production, as shown in Figure 6. In general, those resources that offer the best returns (whether financial or energetic) are exploited first. Attention then turns to resources offering lower returns as production continues. In general the returns offered by an energy resource will depend upon the type of source, formation and depth of the reserve, hostility of the environment, distance from demand centers and any necessary safety or environmental measures. The costs of production often increase exponentially with increases in these factors [22]. The result is that the physical component of the EROI of the resource declines as a function of production. We assume that this decline in EROI, H will follow an exponential decay:

where 0 < Φ ≤ 1.

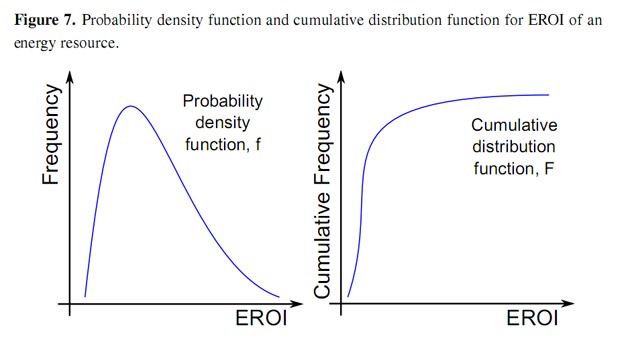

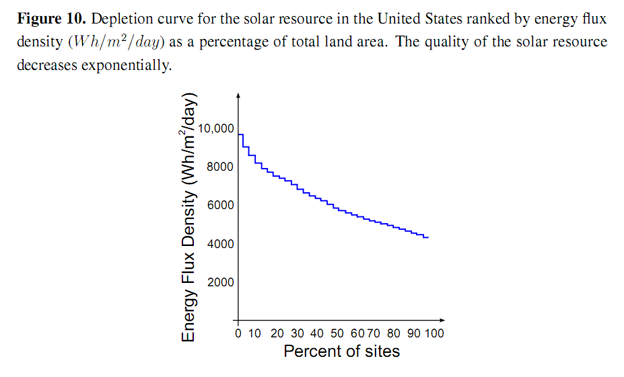

Here (phi) Φ represents the initial value of the physical component and (lower case phi)φ represents the rate of degradation of the resource due to exploitation. Again this rate is assumed constant. We justify this exponential curve by considering the distribution of energy resources. Some of these resources will offer large energy returns due to such factors as their energy density (e.g., grades of crude or coal), their ease of accessibility (e.g., depth of oil resources, on-shore vs. offshore), their proximity to demand centers (e.g., Texan vs. Polar oil) and possible other factors. The EROI of one particular source should be, if not normal, then most likely displays a positive skew, i.e., the median is less than the mean, as depicted in Figure 7. For example, there are more sites with lower average wind speeds than with higher wind speeds.

Unlike non-renewable sources, for which the EROI is solely a function of cumulative production, in the case of renewable energy sources the physical component of EROI is a function of annual production. The technological component will still be a function of cumulative production, which serves as a proxy measure for experience. In this case a reduction in production means that the EROI may “move back up the slope” of this physical component. In the interim, technology, which is a function of cumulative production, will have increased, further pushing up energy returns. This entails that the EROI of a renewable energy source is a path dependent function of production. Decline in the physical component of EROI for renewable energy sources represents the likelihood of the most optimal sites being used earliest. For example, deployment of wind turbines presently occurs only in sites where the average wind speed is above some lower threshold and that are close to large demand centers to avoid the construction of large distribution networks. Over time, the availability of such optimal sites will decrease, pushing deployment into sites offering lower energy returns, which should be reflected in declining capacity factors over time.

3.1 – Supporting Evidence

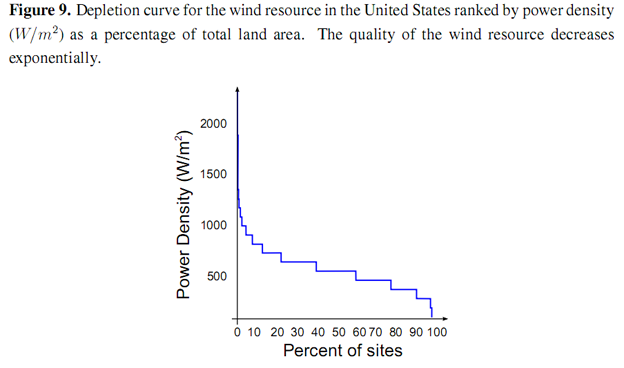

We provide supporting evidence for the EROI function presented by considering wind and solar resources for the US as a case study. The technological component of the EROI may be increased by the production of wind turbines that are able to better extract energy from the passage of air. This increase is subject to an absolute physical limit represented by the Lancaster–Betz limit [23] which defines the maximum proportion of energy that may be extracted from a moving column of air as 16/27 ≅ 60%. Experience curves for wind farms show that long-term costs of energy production from wind have fallen exponentially as a function of cumulative energy production (a proxy for “experience”) [24]. The resource base for wind has been extensively (and intensively) mapped in several regions of the world. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) Western Wind Dataset [25] was used to produce a depletion curve of the US wind resource, ranked by power density (W/m) shown in Figure 9. The power density of the wind resource initially declines exponentially as a function of land area, before dropping sharply below 500 W/m2

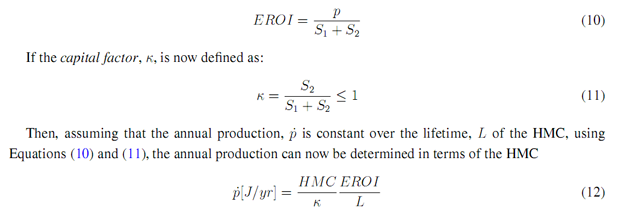

Presently, long-term energy forecasting is done by predicting (or perhaps, more accurately, stipulating) long-term production costs for various energy supply and conversion technologies. This information is then used to optimize a “least-cost” energy system that meets the projected future energy demand. The problems associated with predicting something as volatile as production costs over timescales of decades is rarely discussed. The issue of declining net energy yields is never considered. EROI defines the relationship between the amount of energy that must be embodied as human-made-capital (HMC) in order to produce energy and the amount of energy that HMC can produce. In Section 1.1.1., the EROI was defined as:

We have presented a top-down framework for determining the EROI of an energy source over the entire production cycle of an energy resource. This function allows production costs (in energetic terms) to be predicted into the future. This EROI function, coupled with a purely physical allocation function to allocate energy demand between different energy sources, will allow a new form of energy supply forecasting to be undertaken, based solely on physical principles.

One Comment on "A Dynamic Function for EROI"

BillT on Tue, 28th Feb 2012 3:58 pm

But, if the supporting financial system collapses, all the ‘reserves’ will not matter. No financial system, no oil or other resources. It appears that peak financials will cause the collapse of the energy system soon.